What an Anaphylaxis Action Plan Really Is

An anaphylaxis action plan isn’t just a piece of paper. It’s a clear, step-by-step emergency guide that tells exactly what to do when someone’s body goes into overdrive because of an allergen. This isn’t about a mild rash or a stuffy nose. This is about a reaction that can shut down breathing, crash blood pressure, and kill within minutes. The plan exists so that when panic sets in, someone - a teacher, a coworker, a cafeteria worker - knows exactly what to do without waiting for permission or second-guessing themselves.

Every plan, whether for a child in kindergarten or an adult in a warehouse, has the same core parts: a photo of the person, a list of their confirmed allergens (like peanuts, shellfish, or bee venom), signs of a severe reaction, clear instructions to use epinephrine right away, and emergency contacts. It must be signed by a doctor. No exceptions. A vague note saying "watch for allergies" doesn’t cut it. Lives depend on precision.

Why Epinephrine Is the Only Thing That Matters

There’s no substitute. No antihistamine. No inhaler. No water. Only epinephrine can stop anaphylaxis in its tracks. The CDC and every major allergy group agree: if two body systems are reacting - like hives plus vomiting, or swelling plus trouble breathing - epinephrine goes in immediately. Delaying it increases the chance of death by 83%, according to a 2020 study in the American Family Physician journal.

That’s why every plan must say in bold: Epinephrine first. Not after calling 911. Not after trying Benadryl. Not after waiting to see if it gets worse. Epinephrine is the first step. The ambulance comes after. The auto-injector - whether it’s an EpiPen, Auvi-Q, or generic - must be within arm’s reach at all times. Locked cabinets? That’s a death sentence. Schools in New York State now require epinephrine to be accessible within 60 seconds. Workplaces should follow the same rule.

How Schools Get It Right - and Where They Still Fail

Most U.S. schools have policies because 49 states passed laws requiring them. The CDC’s 2020 guidelines became the blueprint: every student with a known allergy gets a personalized plan, two epinephrine auto-injectors are kept on-site, and at least two staff members per classroom are trained to use them. Some districts even keep stock epinephrine for students without a personal plan - a lifesaver when a child has their first reaction on a field trip.

But here’s the ugly truth: only 37% of schools give annual refresher training. One in five keep epinephrine locked up. Nearly half use outdated forms from five years ago. A parent in Ohio told me her son’s school still had a 2018 plan on file - the allergens were wrong, the emergency contacts were outdated, and the nurse had never been trained on the new Auvi-Q device. That’s not negligence - it’s system failure.

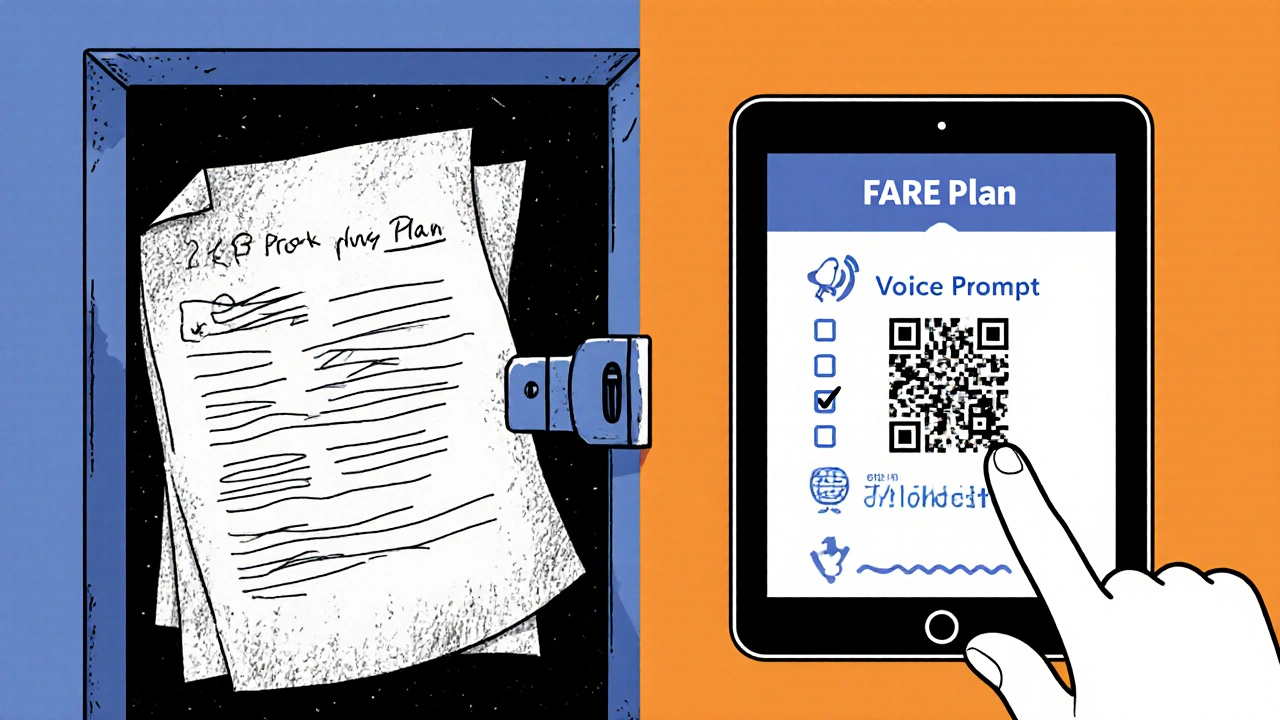

Successful schools don’t just hand out forms. They run drills. They show videos of real reactions. They make sure every bus driver, lunch aide, and substitute knows where the injectors are. One school in California uses QR codes on each plan - scan it and you get a 90-second video of how to use the injector. That’s how you turn paperwork into preparedness.

Workplace Plans? Most Don’t Even Exist

At work, it’s a different story. Only 34% of U.S. employers have any formal anaphylaxis protocol. No federal law requires it. OSHA says employers must provide first aid, but doesn’t say what that means for allergies. That leaves people with severe allergies to fight for their own safety.

Think about a server with a shellfish allergy. They work in a kitchen where cross-contamination is common. Their epinephrine is in a locked drawer behind the counter because the manager says it’s "against policy." When they react, they have to run to the bathroom to inject themselves - and hope someone finds them before they pass out. That’s not an accident. That’s a design flaw.

Even when plans exist, training is weak. A FARE survey found 57% of employees with severe allergies had a reaction where coworkers hesitated to help - and 33% said they were afraid of getting sued. That fear is unfounded. All 50 states have Good Samaritan laws protecting people who give epinephrine in good faith. But if no one’s been told that, they won’t act.

The Must-Have Components of Every Plan

Here’s what a real, usable plan looks like - no fluff, no jargon:

- Photo - so anyone can identify the person quickly

- Confirmed allergens - written by the doctor, not guessed by the parent

- Mild symptoms - itching, hives, runny nose, mild stomach upset

- Severe symptoms - trouble breathing, throat closing, dizziness, fainting, vomiting with breathing issues

- Clear instruction - "Give epinephrine now if any severe symptoms appear"

- Emergency contacts - parent, guardian, or spouse, with phone numbers

- Doctor’s signature and date - plan expires if not updated yearly

That’s it. No extra pages. No legal disclaimers. Just the facts. The FARE template gets a 4.7 out of 5 from school nurses. Generic district forms? Barely 2.8. Why? Because one is made by experts who’ve seen real reactions. The other is made by an administrator who’s never had to use one.

Training Isn’t Optional - It’s the Difference Between Life and Death

Training isn’t a one-time box to check. It’s like fire drills. You don’t wait for the building to catch fire to practice. You do it regularly.

Schools should train all staff for 90 to 120 minutes the first time, then 60 minutes every year. Workplaces should include it in new-hire orientation and annual safety reviews. Training must include:

- How to recognize the difference between a mild reaction and anaphylaxis

- How to use each type of auto-injector - EpiPen, Adrenaclick, generic brands - they all work differently

- How to call 911 while someone is being treated

- What to do after giving epinephrine - lay the person flat, elevate legs if possible, stay with them

One school in Texas trained every janitor and bus driver. When a boy had a reaction on the bus, the driver gave epinephrine in 47 seconds. He was fine. The school didn’t get lucky. They prepared.

What’s Changing in 2025 - And What You Should Do Now

The CDC updated its guidelines again in early 2024, adding rules for field trips, after-school clubs, and sports. FARE launched a digital plan platform that lets families update allergens and contacts in real time - schools in 22% of districts now use it. The FDA is testing new epinephrine injectors with voice prompts - imagine one that says, "Press here. Hold for 3 seconds. The reaction is serious. Call 911."

But you don’t have to wait for technology. Here’s what you can do today:

- If you’re a parent: Demand a signed, current plan from your child’s school. Ask to see where the injectors are stored. Check if staff were trained this year.

- If you’re an employee with allergies: Ask HR for a written accommodation plan. Request that your epinephrine be kept in a known, unlocked location. Offer to lead a 10-minute training for your team.

- If you’re a school or workplace leader: Stop using outdated templates. Use FARE’s 2024 version. Train everyone. Store epinephrine where it’s instantly accessible. Review plans every year.

Real Stories - One Success, One Tragedy

Sarah Johnson’s daughter had a reaction to a peanut-contaminated snack at school. The teacher, trained just weeks before, gave epinephrine in 90 seconds. Called 911. The girl was stable by the time they got to the hospital. No ICU. No long recovery. Just a scared kid who got lucky because her school didn’t cut corners.

On Reddit, a man named Mark wrote: "I had a reaction at my warehouse job. My manager said he didn’t know how to use the injector. I had to call my wife to read the instructions over the phone while I tried to inject myself. I passed out. I woke up in the hospital. They said if I’d waited five more minutes, I wouldn’t have made it. No one had been trained. No one had a plan. I quit that job two weeks later. I’m alive, but I’m not okay."

Final Thought: This Isn’t About Rules - It’s About Responsibility

An anaphylaxis action plan isn’t a legal requirement you check off. It’s a moral promise. A promise that if someone walks into your school or your workplace with a life-threatening allergy, you’ll know what to do if they start to die. It’s not complicated. It’s not expensive. It’s just about doing the right thing - before it’s too late.

9 Comments