Post-Transplant Complication Risk Calculator

Complications after organ transplantation often stem from immune responses, particularly when rejection occurs. The severity and timing of rejection episodes influence overall health outcomes.

- Acute rejection (within first 3 months) typically requires immediate treatment but can often be reversed with higher immunosuppression.

- Chronic rejection develops over time and leads to progressive organ dysfunction and long-term complications.

- Higher doses of immunosuppressive drugs increase infection risk but help prevent rejection.

- Organ-specific complications vary-e.g., cardiac allograft vasculopathy in heart transplants or post-transplant diabetes mellitus in kidney transplants.

When a new organ takes over, the body can see it as an invader. Organ rejection is a immune response that attacks the transplanted tissue, potentially setting off a chain of health problems after surgery. Understanding why this happens, and how it fuels later issues, is key for patients, families, and clinicians alike.

What Exactly Is Organ Rejection?

Organ rejection occurs when the recipient’s immune system recognizes foreign proteins on the donor organ and launches an attack. The process involves T‑cells, antibodies, and inflammatory chemicals that try to destroy the graft. Without proper control, the new organ can fail, and a host of secondary complications may arise.

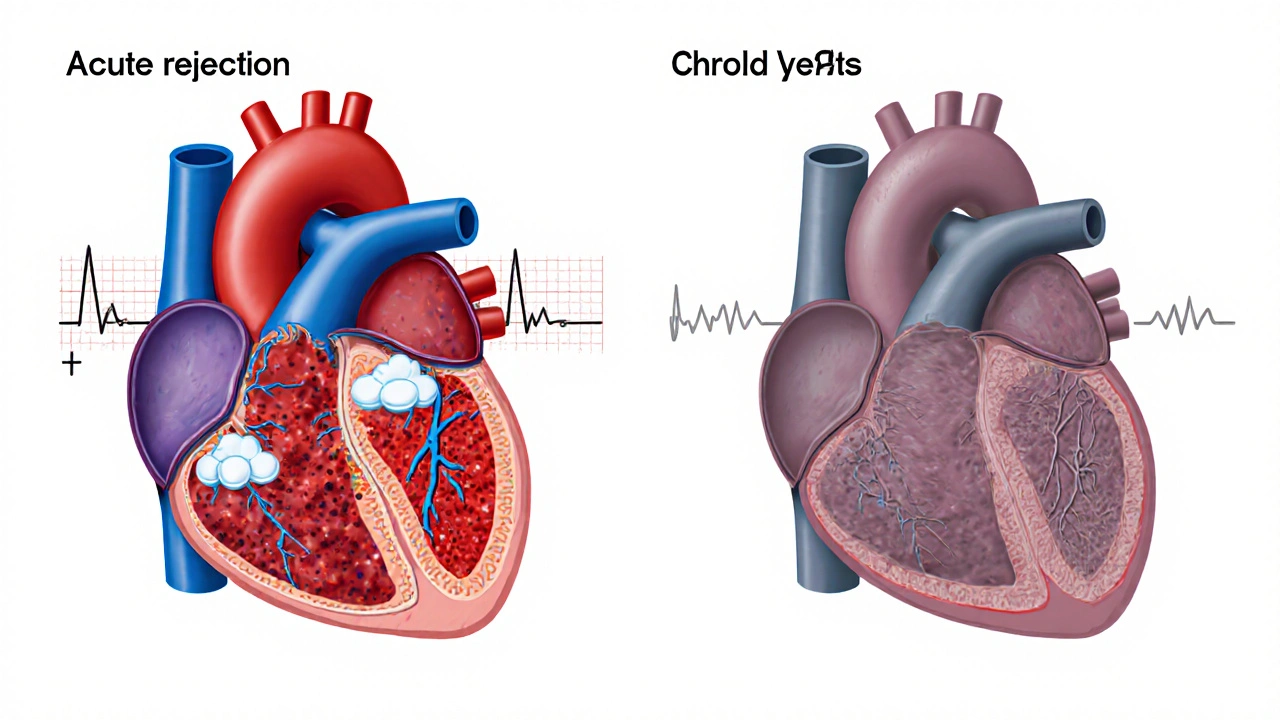

Acute vs. Chronic Rejection - Two Different Faces

| Aspect | Acute Rejection | Chronic Rejection |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Days to weeks after transplant | Months to years later |

| Immune Mechanism | Predominantly T‑cell mediated | Combination of immune injury and vascular remodeling |

| Symptoms | Fever, pain at graft site, loss of function | Gradual decline in organ performance, hypertension |

| Treatment | High‑dose steroids, antibody‑based therapy | Adjusted immunosuppression, possible re‑transplant |

| Long‑term Risk | Can lead to chronic injury if uncontrolled | Often the main cause of late graft loss |

Both forms can spark wider health problems, but chronic rejection is the biggest driver of long‑term graft failure.

How Rejection Sets Off Post‑Transplant Complications

Once the immune system is activated, several pathways open that affect the whole body:

- Inflammation damages blood vessels inside the graft, leading to graft vasculopathy - a thickening of the vessel walls that reduces blood flow and oxygen delivery.

- Immune‑mediated injury forces clinicians to boost immunosuppressive therapy-drugs that dampen the immune response to protect the organ. Higher drug doses, however, raise the risk of infection and metabolic side effects.

- Rejection episodes often trigger the release of cytokines that can impair kidney function, raise blood pressure, and disturb glucose metabolism.

These ripple effects explain why patients frequently see a cluster of complications after a rejection event.

Common Post‑Transplant Complications Linked to Rejection

Below are the most frequently observed problems and why rejection makes them more likely:

- Infections - The same drugs used to prevent rejection also suppress the body’s ability to fight bacteria and viruses. Opportunistic infections such as Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infectionare especially common in the first six months after a transplant can further inflame the graft.

- Post‑transplant Diabetes Mellitus (PTDM) - Steroids and calcineurin inhibitors raise blood sugar levels. When rejection forces higher steroid bursts, the chance of PTDM spikes dramatically.

- Hypertension - Both graft vasculopathy and certain immunosuppressants (like tacrolimus) narrow blood vessels, leading to persistent high blood pressure that can damage the heart and kidneys.

- Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy (CAV) - In heart transplants, chronic immune injury produces diffuse coronary artery disease, a hallmark of long‑term rejection.

- Renal Dysfunction - Even in non‑kidney transplants, the high‑dose drugs used during rejection can be nephrotoxic, reducing the kidney’s filtering ability.

Monitoring - Spotting Rejection Before It Triggers Bigger Problems

Early detection is the best defense. Most transplant centers use a blend of lab tests, imaging, and tissue biopsies:

- Blood biomarkers - Rising serum creatinine (for kidney), troponin (for heart), or liver enzymes can signal organ stress.

- Donor‑specific antibodies (DSA) - Presence of antibodies against donor HLA antigens often precedes chronic rejection.

- Routine biopsies - A small tissue sample examined under a microscope can catch subtle immune activity before function declines.

- Imaging - Ultrasound, CT, or MRI can reveal vascular narrowing from graft vasculopathy.

Patients should also track symptoms such as unexplained fever, swelling, or new‑onset pain around the graft site and report them immediately.

Prevention and Management Strategies

Balancing graft protection with side‑effect risk is a tightrope walk. Here are the most effective approaches:

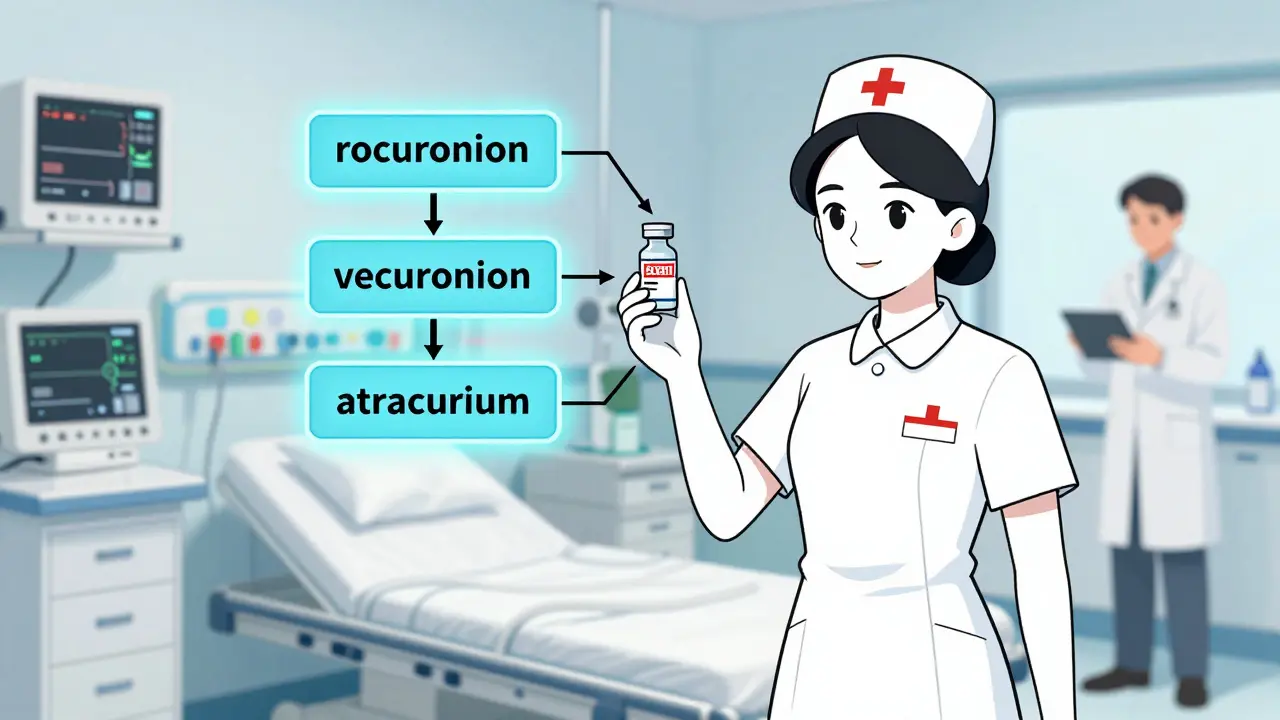

- Tailored Immunosuppression - Using the lowest effective dose of calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites, and steroids reduces infection risk while still curbing rejection.

- Prophylactic Antivirals - CMV prophylaxis (e.g., valganciclovir) for the first three months cuts down viral reactivation rates.

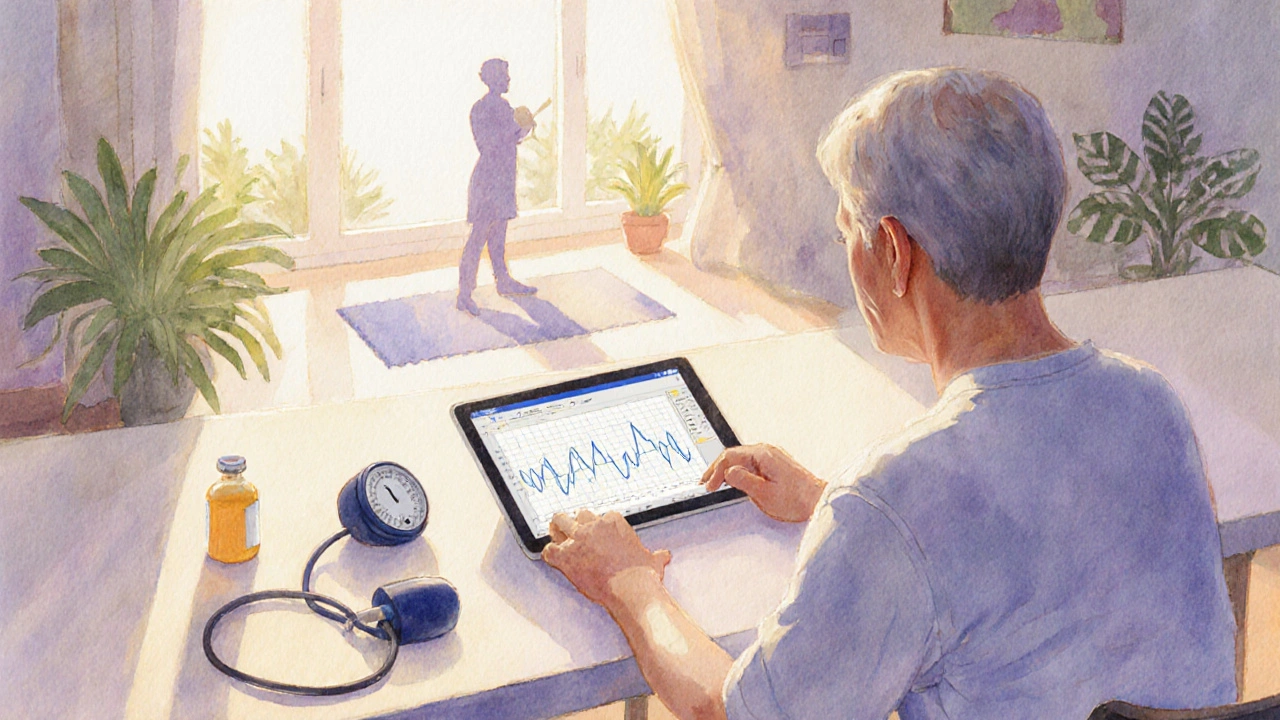

- Metabolic Monitoring - Regular glucose checks, blood pressure readings, and lipid panels catch PTDM and hypertension early, allowing prompt lifestyle or medication adjustments.

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) - Measuring blood levels of drugs like tacrolimus ensures doses stay within a therapeutic window, preventing toxicity.

- Patient Education - Empowering patients to adhere to medication schedules, recognize warning signs, and maintain a healthy diet and exercise routine reduces long‑term complications.

Practical Checklist for Patients

- Take immunosuppressants exactly as prescribed; set alarms if needed.

- Log daily blood pressure and fasting glucose; share trends with your transplant team.

- Attend all scheduled lab draws, imaging, and biopsy appointments.

- Watch for fever, unexplained pain, swelling, or sudden changes in organ function.

- Maintain good hygiene, avoid crowds during peak flu season, and get recommended vaccinations (e.g., flu, pneumococcal).

- Stay hydrated, follow a low‑salt diet, and engage in moderate exercise as approved by your doctor.

- Keep a written list of all medications, including over‑the‑counter drugs, to avoid harmful interactions.

Following this routine can dramatically lower the odds that an early rejection episode spirals into chronic graft loss or severe metabolic problems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I stop my immunosuppressive drugs after a successful transplant?

No. Stopping the medication or cutting the dose dramatically raises the chance of acute rejection, which can quickly damage the new organ and trigger many downstream complications.

How soon after surgery do rejection episodes usually appear?

Acute rejection most often shows up in the first 30‑90 days, while chronic rejection may not become evident until a year or more after the transplant.

What are the early signs of graft vasculopathy?

Patients may notice reduced organ performance (e.g., decreased urine output for kidney, shortness of breath for heart) and rising blood pressure. Imaging studies often reveal narrowing of the graft’s blood vessels before symptoms become severe.

Is CMV infection always dangerous after transplant?

CMV can be mild or severe. In immunocompromised patients, it can cause fever, organ inflammation, and even trigger rejection. Prophylactic antiviral therapy and regular monitoring keep serious cases rare.

What lifestyle changes help lower post‑transplant complications?

A balanced diet low in sodium and refined sugars, regular moderate exercise, avoiding smoking, and staying up‑to‑date with vaccinations all reduce infection risk, hypertension, and metabolic problems.

15 Comments