When a doctor writes a prescription for a brand-name medication, they don’t just think about what works best for the patient-they also think about whether the insurer will even pay for it. That’s the new reality in healthcare. Insurers, especially large ones like UnitedHealthcare, Cigna, and CVS Health/Aetna, have spent the last 15 years tightening their grip on drug costs. Their tool? Generic drug substitution. It’s not just a suggestion anymore. It’s a rule. And providers are the ones stuck in the middle.

How Insurers Force Generic Substitutions

Insurers don’t just encourage generics-they enforce them. The system is built on tiers. Generic drugs sit in Tier 1: $5 to $15 copay. Brand-name drugs without a generic version? Tier 3 or 4: $40 to $100+ copay. Sometimes, the patient pays 50% of the cost. That’s not a nudge. That’s a wall. But it goes deeper. Many insurers now use formulary exclusions-meaning the brand-name drug is simply not covered at all. If a patient needs it, they have to pay full price. Or they use step therapy: you must try the generic first, fail on it, then get approval for the brand. And prior authorization? That’s the gatekeeper. Doctors must submit paperwork, often within 72 hours, justifying why the patient can’t take the cheaper version. If they don’t, the prescription gets denied. In 2022, 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were generics. That’s not a coincidence. It’s the result of these systems. Insurers say they saved billions. The FDA says generics cost 80-85% less. And for most drugs, that’s true. But not all drugs are created equal.What Providers See on the Ground

Doctors aren’t just frustrated-they’re overwhelmed. A 2023 MGMA survey found physicians spend an average of 16.9 minutes per prior authorization request. That’s nearly three hours a day, just filling out forms. One Mayo Clinic doctor in Minnesota told the AMA about a patient with a history of GI bleeding. The insurer denied coverage for the brand-name anticoagulant because the generic was technically “bioequivalent.” The patient had to wait 22 days through three appeals. During that time, they had two emergency room visits for internal bleeding. It’s not just rare cases. A Reddit post from a cardiologist in May 2024, with over 140 upvotes, said they now add “medical necessity” notes to every brand-name prescription-just to avoid delays. That’s added 40% more time to every prescription they write. Some providers have adapted. Many now use templated letters for common exceptions. Others hire dedicated staff. Medium-sized practices report spending $112,400 a year per full-time employee just to handle prior authorizations. That’s not clinical care. That’s paperwork.The Clinical Risks No One Talks About

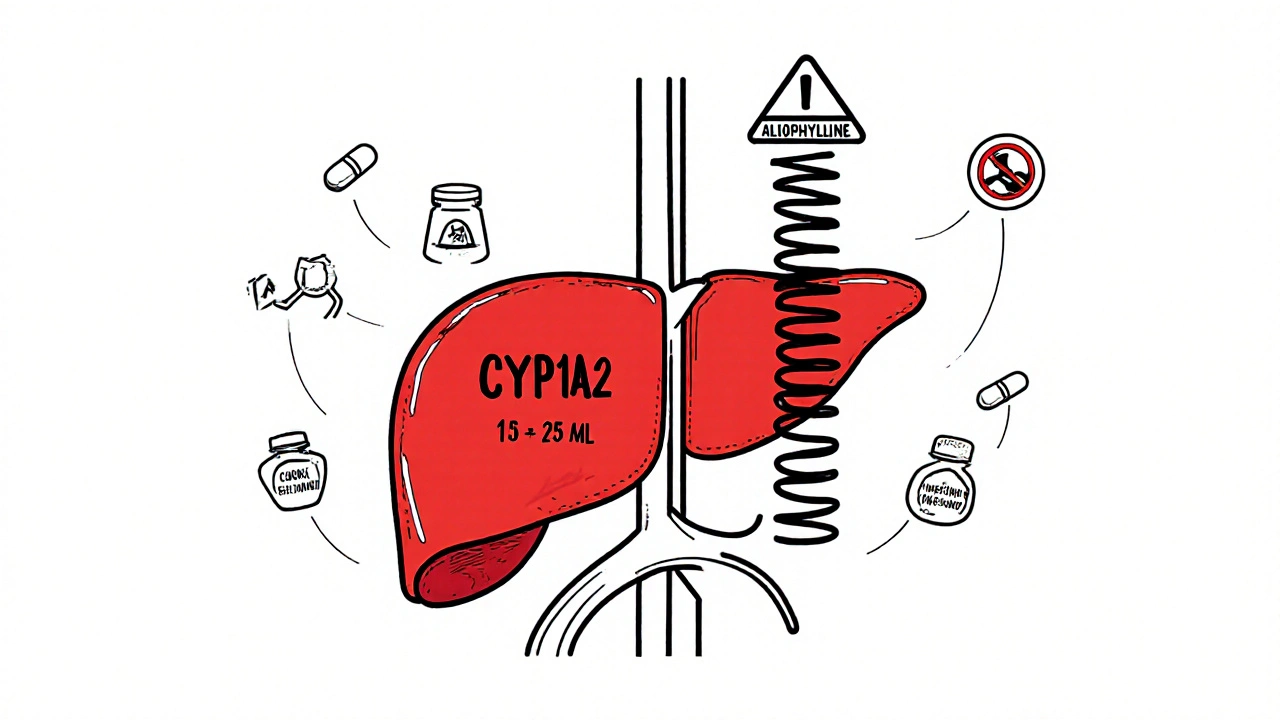

The FDA says generics must be within 80-125% of the brand-name drug’s absorption rate. That’s a huge window. For most drugs, it doesn’t matter. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like levothyroxine, warfarin, or seizure meds-small differences can mean big problems. The American Medical Association reports that 28% of physicians have seen adverse outcomes after switching patients from brand to generic for these drugs. One patient might switch from Synthroid to a generic levothyroxine and suddenly feel exhausted, gain weight, or have heart palpitations. The doctor says, “It’s the same drug.” The insurer says, “It’s cheaper.” The patient says, “I don’t feel right.” And now they’re off their medication. Dr. Arthur Caplan from NYU points out that the 80-125% range was never meant for drugs where a 5% change in blood level could trigger a seizure or a stroke. Yet insurers don’t adjust their rules. They just keep pushing.

State Laws Are Starting to Push Back

Not all states are letting insurers run unchecked. California’s AB 347, effective January 2024, forces insurers to approve step therapy exceptions within 72 hours if the doctor provides clinical documentation. Approval rates jumped to 92% on first try. In Arizona, HB 2175-signed in May 2025-bans insurers from using AI alone to deny care. Medical directors must personally review each denial. That rule kicks in by June 2026. These aren’t just nice-to-haves. They’re lifesavers. One California psychiatrist said since AB 347, their approval times dropped from 14 days to under 72 hours. That’s the difference between a patient staying on their medication and dropping out.How Providers Are Fighting Back

Doctors aren’t passive. They’ve built strategies:- Preemptive documentation: Adding clinical notes to every brand-name script, even if they think it won’t be challenged.

- EHR integration: Using electronic prior authorization (ePA) systems that auto-fill forms and cut approval time by 55%, according to a 2024 JAMIA study.

- Building relationships: Knowing which case manager at which insurer responds fastest. Calling them directly. Sometimes, that’s the only way.

- Advocacy: Joining state medical associations pushing for reform. The AMA’s 2023 position paper says insurer overuse of prior authorization has led to patient deaths.

The Bigger Picture: Who Controls the System?

Behind the insurers are Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, OptumRx. These companies control 85% of formularies for insured Americans. They negotiate rebates with drugmakers. The more generics they push, the more money they make. And many PBMs are owned by the same companies that run the insurers. It’s a closed loop. In 2023, 76% of private insurance plans required mandatory generic substitution. That’s up from 28% in 2010. For chronic conditions like high blood pressure, it’s 92%. For specialty drugs like biologics? Only 45%. Why? Because those drugs don’t have generics yet. But when they do, the pressure will come.What’s Next?

The federal Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act already requires Medicare Advantage plans to respond to prior authorization requests in 72 hours for urgent cases. By 2027, all Medicare and Medicaid plans must use standardized ePA systems. That could cut processing time by 40-60%. But here’s the catch: speed doesn’t fix bad rules. If the criteria are still vague-if insurers still define “medical necessity” without telling providers what that means-then faster systems just mean faster denials. Some insurers are experimenting with “value-based formularies,” where they prefer certain brand-name drugs based on real-world outcomes. That’s a step forward. But it’s rare. Most still rely on cost alone.Bottom Line: The System Is Broken, But Not Hopeless

Insurers aren’t evil. They’re responding to real cost pressures. Generic drugs save billions. But when the system ignores individual patient needs, it fails. Doctors aren’t resisting generics-they’re resisting being forced to make clinical decisions based on spreadsheets, not science. Providers are adapting. They’re documenting more. They’re fighting back. They’re pushing for laws that protect patients. But they can’t do it alone. Until insurers stop treating every patient like a line item on a balance sheet, the system will keep hurting the people it’s supposed to help.Are generic drugs always safe to substitute for brand-name drugs?

For most medications, yes. Generics are required by the FDA to be bioequivalent to brand-name drugs. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like levothyroxine, warfarin, or certain anti-seizure medications-even small differences in absorption can cause problems. Studies show 28% of physicians have seen adverse outcomes after switching patients to generics in these cases. Always discuss potential risks with your doctor before switching.

Why do insurers require step therapy before approving brand-name drugs?

Step therapy is a cost-control tactic. Insurers want patients to try the cheapest option first, even if it’s not the best fit. If the patient doesn’t respond or has side effects, they can then request the brand-name drug. But this delays treatment and can lead to worsening conditions. Some states, like California, now require insurers to approve exceptions within 72 hours if the doctor provides clinical evidence.

How long does prior authorization usually take?

It varies. For urgent cases, federal law requires Medicare Advantage plans to respond within 72 hours. For non-urgent requests, insurers often have up to 5 business days. But many still take longer, especially if paperwork is incomplete. Electronic prior authorization (ePA) systems have cut approval times by 55%, but manual systems can drag on for weeks.

Can I ask my doctor to prescribe only generics?

Yes, and many doctors will if it’s appropriate. But not all generics work the same for every patient. Some people respond better to one brand of levothyroxine than another, even if both are generic. If you’ve had issues with a generic before, tell your doctor. They can write “dispense as written” or “no substitution” on the prescription to prevent automatic switching at the pharmacy.

What’s the difference between an insurer and a PBM?

Your insurer (like UnitedHealthcare or Aetna) pays for your coverage. A Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM)-like CVS Caremark or OptumRx-manages your drug benefits. They decide which drugs are covered, set copays, and negotiate rebates with drugmakers. Many PBMs are owned by the same companies that run insurers, creating a conflict of interest where cost savings for the company can override patient needs.

11 Comments