When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, you’d expect generic versions to flood the market right away-lower prices, more choices, better access. But that’s not what usually happens. Instead, one generic company gets a 180-day exclusivity window, blocking everyone else from selling the same drug. This isn’t a loophole. It’s federal law. And it’s shaped how billions of dollars in drug spending flow in the U.S. every year.

Why Does This 180-Day Rule Even Exist?

The answer goes back to 1984, when Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, generic drug makers had to repeat every single clinical trial the brand-name company did. It was expensive, slow, and discouraged competition. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It let generic companies submit Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs)-basically, saying, "This drug is the same as the brand, no need to redo all the tests." But there was a catch. Generic companies had to prove the brand’s patents were invalid or not being infringed. That meant lawsuits. Big ones. Costing millions. So Congress gave them a reward: 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version after approval. No one else could enter the market during that time. The goal? Encourage the first generic company to take the legal risk.Who Gets the 180 Days? It’s Not Who You Think

It’s not about who files first overall. It’s about who files the first ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. That’s the legal notice saying, "We believe your patent is invalid or we don’t infringe it." If two companies file on the same day, the FDA has rules to pick the winner-usually based on who submitted the most complete application first. Courts have backed this up. In Granutec, Inc. v. Shalala, the Fourth Circuit ruled that only the first applicant with a substantially complete ANDA gets the clock. Here’s the kicker: the exclusivity doesn’t start when the FDA approves the drug. It starts when the generic hits the market-or when a court rules the patent is invalid or not infringed. Whichever comes first. That’s why some companies wait. They file the ANDA, then sit on it while they fight the patent in court. If they win, the clock starts. If they lose, they get nothing. And if they delay commercialization too long, they can lose the exclusivity entirely.The Big Problem: The Clock Can Stop for Years

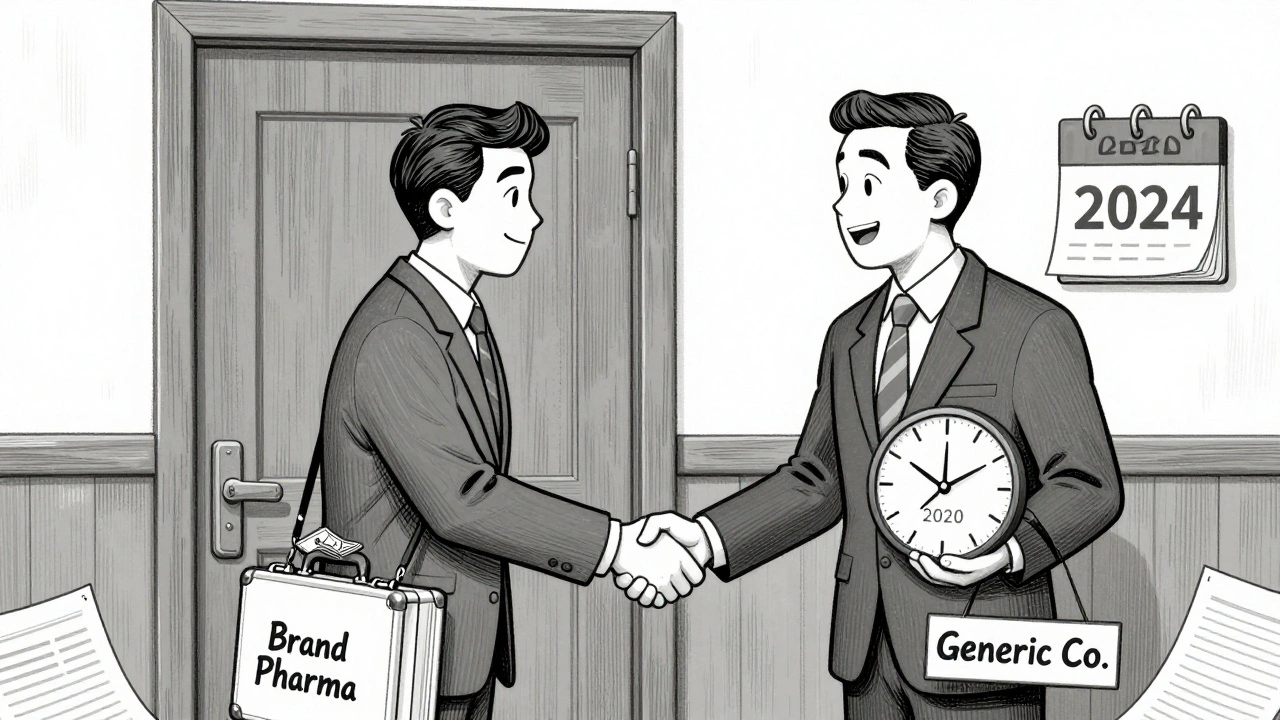

This is where the system breaks. Sometimes, the first generic company doesn’t launch right away. Why? Because they’ve struck a deal with the brand-name company. In exchange for staying off the market, they get paid-sometimes millions. These "pay-for-delay" settlements are legal, but they’re controversial. They delay competition. They keep prices high. And they directly undermine the whole point of the 180-day rule: to bring down drug costs fast. Even without settlements, the clock can drag. Patent lawsuits take years. The FDA doesn’t approve the generic until the legal mess clears. So a drug might have a patent expire in 2020, but the first generic doesn’t launch until 2024. That’s four years of monopoly pricing. And during those years, no other generic can enter. The 180-day exclusivity becomes a 4-year delay, with just 180 days of competition at the end. The FDA noticed. In March 2022, they proposed a fix: make the exclusivity period start only when the generic is actually sold. No more sitting on the approval. If the first applicant waits two years to launch, the 180 days don’t start until then. That means the clock runs for 180 days after launch-not 180 days after a court decision that happened years ago. This would force companies to move faster or lose the benefit.

What Happens If You Mess Up?

It’s not enough to file the right paperwork. The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 added forfeiture rules. If you don’t market your generic within 75 days of FDA approval-or if you withdraw your application, or if you fail to get approval within 30 months of filing-you can lose your exclusivity. The FDA made this clear in a 2018 letter about buprenorphine/naloxone. They said: if you don’t start selling, you’re out. No second chances. This has led to a legal arms race. Generic companies now hire teams of lawyers just to track deadlines. One missed date, one incomplete filing, one court misstep-and you’re out. The stakes? For a blockbuster drug like Lipitor or Humira, that 180-day window could be worth over $1 billion in sales. No wonder companies fight over who gets it.How This Compares to Other Exclusivity Rules

The 180-day rule is different from other drug exclusivities. The FDA also gives:- 5 years of exclusivity for a brand-new chemical compound (new chemical entity)

- 3 years for new clinical studies on existing drugs

- 6 months extra for pediatric testing

Why This Matters to You

If you take a generic drug, this system affects your out-of-pocket cost. When 180-day exclusivity is active, prices drop sharply-often by 80% or more. But if the first company delays launch, you pay brand prices for years. That’s why consumer groups and state Medicaid programs watch these exclusivity filings closely. When a generic finally enters, it can save millions in public health spending. In 2024, generic drugs saved U.S. patients an estimated $1.7 trillion over the past decade. A big chunk of that came from 180-day exclusivity driving competition. But if the system is gamed, those savings vanish.What’s Next?

The FDA’s 2022 proposal is still under review. If passed, it would be the biggest change to Hatch-Waxman in 20 years. It could end the practice of sitting on exclusivity while waiting for patent lawsuits to resolve. It might also reduce pay-for-delay deals by removing the incentive to delay. Some experts think the FDA should go further: make the exclusivity period 270 days instead of 180 if the first applicant launches more than five years before the patent expires. Others want to let multiple first applicants share the exclusivity. But for now, the system remains a high-stakes game of legal chess.Bottom Line

The 180-day exclusivity rule was meant to speed up generic access. But it’s become a tool for delay. It rewards legal risk-but only if you play it right. And too often, the winners aren’t patients. They’re companies that know how to navigate the loopholes. Until the rules change, the cheapest drug isn’t always the one that hits the market first. It’s the one that finally breaks through the legal wall.What triggers the start of the 180-day exclusivity period for a generic drug?

The 180-day exclusivity period begins on the earliest of two dates: the date the first generic company starts selling the drug commercially, or the date a federal court rules that the brand’s patent is invalid or not infringed. It does not start when the FDA approves the drug-only when one of these two events happens.

Can a generic company lose its 180-day exclusivity?

Yes. Under the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, a company can forfeit its exclusivity if it fails to market the drug within 75 days of FDA approval, withdraws its application, or doesn’t receive approval within 30 months of filing. The FDA has explicitly stated that failure to commercialize results in loss of exclusivity, even if the company was the first to file a Paragraph IV certification.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement included in an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) that challenges the validity or infringement of a patent listed for the brand-name drug in the FDA’s Orange Book. Only applicants who submit this certification are eligible for the 180-day exclusivity incentive.

Why do brand-name and generic companies sometimes settle patent lawsuits?

Brand-name companies sometimes pay generic companies to delay market entry, known as "pay-for-delay" settlements. The generic company agrees to hold off launching its version, and in return, receives a payment or other benefit. These deals keep prices high and undermine the purpose of the 180-day exclusivity rule, which is to encourage competition.

How does the 180-day exclusivity differ from biosimilar exclusivity?

The 180-day exclusivity under Hatch-Waxman is a winner-takes-all incentive for the first generic company to challenge a patent. In contrast, biosimilars under the BPCIA can have multiple first applicants, and the first interchangeable biosimilar gets 12 months of exclusivity. Unlike the generic system, biosimilar exclusivity doesn’t require a patent challenge-it’s based on regulatory approval and interchangeability.

What was the FDA’s 2022 proposal to fix the 180-day exclusivity system?

In March 2022, the FDA proposed changing the law so that the 180-day exclusivity period only starts when the first generic company begins commercial marketing. Under current rules, the clock can start years earlier based on a court decision, allowing the company to delay launch and block competition. The proposal would ensure exclusivity lasts exactly 180 days after launch, not 180 days after a court ruling that happened years ago.

10 Comments