When antibiotics vanish, infections don’t wait

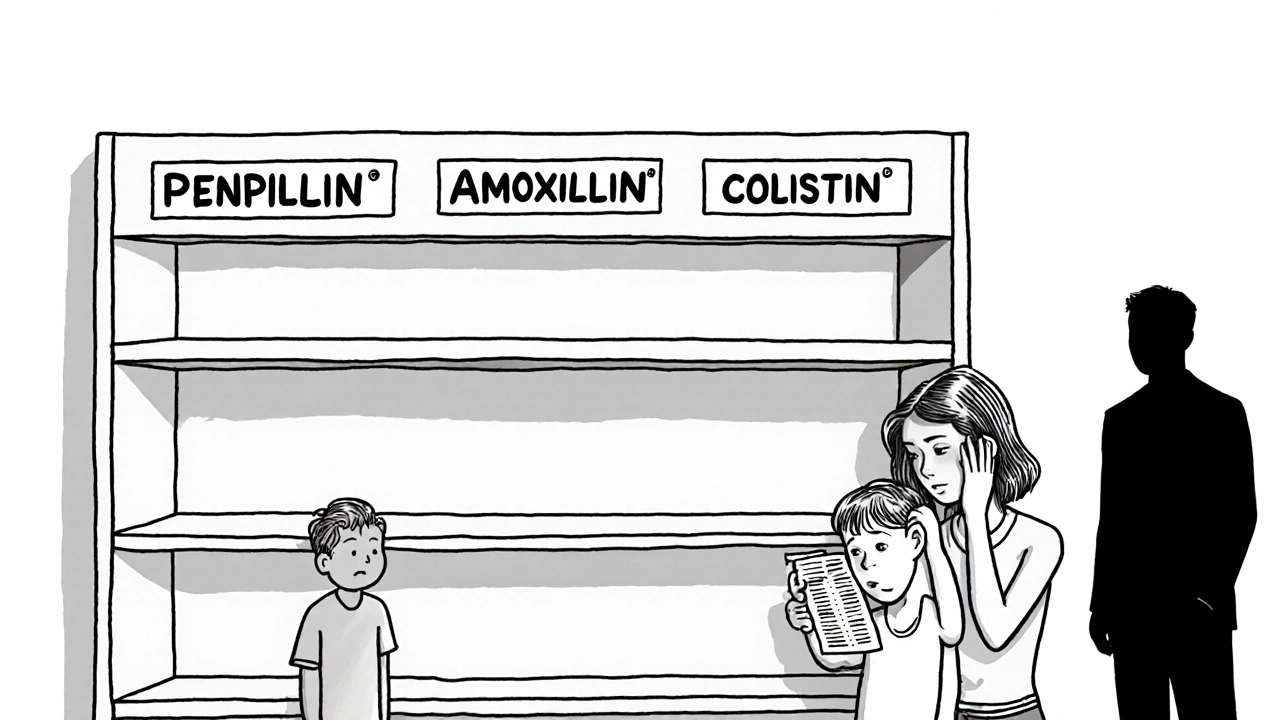

Imagine needing a simple antibiotic for a urinary tract infection - something your doctor has prescribed for years - but the pharmacy has none. Not just out of stock. Completely gone. No backorder. No substitute that works as well. That’s not a hypothetical. It’s happening right now in hospitals from Sydney to São Paulo, from rural Kenya to inner-city Detroit.

Antibiotics aren’t like painkillers or blood pressure meds. When they disappear, there’s often no backup. You can’t swap penicillin for ibuprofen and call it a day. If the right antibiotic isn’t there, an infection doesn’t just get worse - it can kill. And the number of people facing this reality is growing fast.

Why are antibiotics running out?

It’s not one problem. It’s a perfect storm.

First, making antibiotics isn’t profitable. Generic antibiotics - the kind most people need - cost pennies. A single dose of amoxicillin might sell for less than 10 cents. But the cost to make it safely? Regulatory standards, sterile labs, quality checks - those add up. Manufacturers have to invest millions to meet global standards. When the profit margin is razor-thin, companies walk away. Why make a drug that earns $200,000 a year when you can make a cancer drug that earns $200 million?

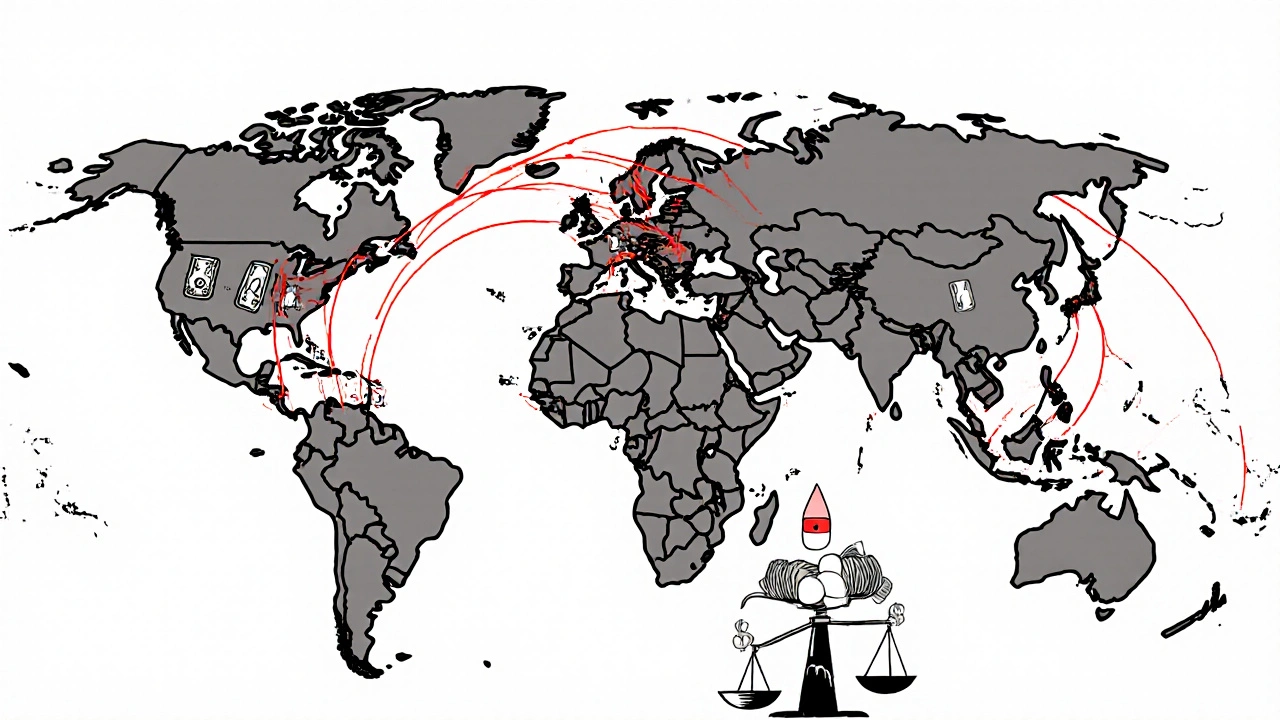

Second, global supply chains are fragile. Over 80% of the active ingredients in antibiotics come from just two countries: India and China. Any disruption - a factory shutdown, a trade dispute, a shipping delay - ripples across the world. Brexit alone pushed UK antibiotic shortages from under 700 in 2020 to over 1,600 in 2023. In the U.S., shortages hit a 10-year high in 2024. The European Economic Area reports 28 countries are dealing with shortages, 14 of them calling them “critical.”

Third, demand is rising while supply shrinks. Antibiotic-resistant infections are climbing. In 2023, one in three urinary tract infections couldn’t be treated with first-line drugs. Doctors are forced to use stronger, riskier antibiotics - which then become overused and lose effectiveness too. It’s a cycle: shortages push doctors to use broader-spectrum drugs, which speeds up resistance, which creates more shortages.

What’s running out - and who’s feeling it?

It’s not just one or two drugs. Over 37 antimicrobials are officially listed as in short supply globally. Some of the most critical:

- Penicillin G benzathine - essential for treating syphilis and preventing rheumatic fever. Has been scarce since 2015.

- Amoxicillin - the go-to for ear infections, pneumonia, and strep throat. Shortages in 2023 cut its use by over half in some countries.

- Cephalosporins - used for serious infections. When they vanish, doctors turn to carbapenems, which are last-resort drugs that accelerate resistance.

- Colistin - a toxic, last-ditch antibiotic now being used for routine UTIs because nothing else is available.

These aren’t just hospital problems. In rural Kenya, nurses report sending children home without antibiotics because penicillin isn’t there. In Mumbai, a mother’s child waited 72 hours for azithromycin - the delay led to pneumonia complications requiring ICU care. In California, doctors told the APHA forum they’re using colistin for simple infections. That’s not innovation. That’s desperation.

The ripple effect: More infections, more deaths

When antibiotics vanish, patients don’t just wait longer. They get sicker. They stay in hospitals longer. They need more tests. More IVs. More surgeries. More money. And more die.

Surveys show 78% of U.S. hospital pharmacists had to change treatment plans in the past year because of shortages. Sixty-two percent saw more complications - longer fevers, more readmissions, more sepsis cases. In low-income countries, 70% of people already can’t access basic antibiotics. When shortages hit, it’s not a delay - it’s a death sentence.

The WHO calls this a “syndemic” - a deadly mix of under-treatment and rising resistance. In places with weak health systems, people die from infections that were curable 50 years ago. In high-income countries, we’re slowly losing ground. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance predicts that without major changes, antibiotic shortages will cause 1.2 million extra deaths a year by 2030.

What hospitals are doing - and what’s working

Hospitals aren’t sitting idle. Many have set up antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) - teams that track antibiotic use, spot shortages early, and find smarter ways to use what’s left.

Johns Hopkins Hospital cut unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 37% during shortages by using rapid diagnostic tests. Instead of guessing what’s causing an infection, they test first. That means fewer drugs used, less resistance, and less strain on supply.

California created a regional antibiotic-sharing network. Hospitals pool their remaining stock. If one hospital runs out of amoxicillin, another nearby can send it. That cut critical shortage impacts by 43% across participating sites.

But these solutions aren’t easy. Setting up an ASP takes 6 to 12 months. Pharmacists are spending 22% more time managing shortages. Rationing decisions are heartbreaking - who gets the last dose? A 7-year-old with pneumonia? An elderly patient with sepsis? There’s no good answer.

Why this isn’t just a healthcare problem

This isn’t just about doctors and pharmacies. It’s about economics, policy, and global fairness.

The global antibiotic market was worth $38.7 billion in 2024 - but grew just 1.2% since 2019. Meanwhile, the rest of the pharmaceutical industry grew at 5.7%. Why? Because antibiotics aren’t profitable. Drugmakers invest in chronic disease drugs that patients take for life. Antibiotics? You take them for 7 days. Then you’re done.

Regulators are waking up. The U.S. FDA approved two new manufacturing facilities in early 2025 - expected to ease 15% of shortages by late 2025. The WHO launched a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative. The European Commission is pushing new rules to guarantee production.

But these are band-aids. The real fix? Pay manufacturers enough to make antibiotics safely. Reward innovation. Stop letting low prices kill people. And make sure every country - rich or poor - has access.

What you can do

You can’t fix the supply chain. But you can help stop the cycle.

- Don’t demand antibiotics. If your doctor says it’s a virus, believe them. Antibiotics don’t work on colds or flu.

- Take them exactly as prescribed. Never skip doses. Never save leftovers. Never share them.

- Support policies that fund antibiotic production. Write to your representatives. Ask why we’re not investing in the drugs that save lives.

Antibiotics are one of humanity’s greatest inventions. But they’re not infinite. If we keep treating them like disposable commodities, we’ll lose them - and with them, the ability to treat the most basic infections.

Why are antibiotics more likely to be in short supply than other drugs?

Antibiotics are 42% more likely to face shortages than other medications because they’re cheap to make, hard to profit from, and require expensive, sterile manufacturing. Unlike cancer or diabetes drugs, which patients take for years, antibiotics are used for days - so manufacturers have little financial incentive to keep producing them. Plus, most are generic, meaning prices have dropped 27% since 2015, squeezing margins even further.

Can I just use an older or stronger antibiotic if my usual one is out of stock?

No. Antibiotics are targeted. Using a stronger or broader-spectrum drug when it’s not needed speeds up resistance. For example, if amoxicillin is gone and you take a carbapenem instead, you’re exposing bacteria to a last-resort drug - which can make future infections untreatable. Only switch antibiotics under a doctor’s guidance, and only if no other safe option exists.

Are there any alternatives to antibiotics when they’re unavailable?

For bacterial infections, there are no reliable alternatives. Antivirals don’t work on bacteria. Herbal remedies, probiotics, or essential oils have no proven effect against serious infections like pneumonia, sepsis, or meningitis. In some cases, doctors may delay treatment while waiting for diagnostics - but that’s risky. Antibiotics are the only proven treatment. When they’re gone, the options are limited to supportive care - fluids, oxygen, monitoring - which isn’t enough for many infections.

Why can’t we just import more antibiotics from other countries?

Many countries are already facing their own shortages. The U.S. imports over 80% of its antibiotic ingredients from India and China - but those countries are also struggling with production issues, regulatory delays, and domestic demand. Importing isn’t a fix - it’s a temporary patch. Plus, different countries have different standards. A drug approved in one country might not meet safety rules in another, making cross-border shipments legally and medically risky.

Is antibiotic resistance making shortages worse?

Yes - and it’s a vicious cycle. When first-line antibiotics run out, doctors are forced to use stronger ones. That overuse speeds up resistance. As resistance grows, more drugs become useless, shrinking the pool of effective antibiotics. That means even more shortages. In 2023, over 40% of E. coli infections were resistant to common antibiotics. When the drugs that used to work no longer do, shortages become deadly.

What’s being done to fix this long-term?

The WHO is pushing a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative to fund manufacturing and stockpiling by 2027. The U.S. FDA is approving new production facilities. The European Union is reforming drug pricing to guarantee manufacturers can make antibiotics profitably. But progress is slow. Real change requires governments to pay more for antibiotics - even if they’re cheap - so companies have reason to keep making them. Without that, shortages will keep growing.

What happens next?

If nothing changes, antibiotic shortages will rise 40% by 2030. That means more deaths from simple infections. More kids dying from ear infections that turn to meningitis. More mothers losing children to pneumonia because the right drug wasn’t there. More hospitals overwhelmed by sepsis cases they can’t treat.

This isn’t a problem for the future. It’s happening now. And the fix isn’t just about making more pills. It’s about valuing life over profit. It’s about recognizing that a $0.10 antibiotic is worth more than a $10,000 cancer drug - because without it, none of us are safe.

9 Comments