Hepatitis‑Related Liver Cancer Risk Calculator

Enter Your Information

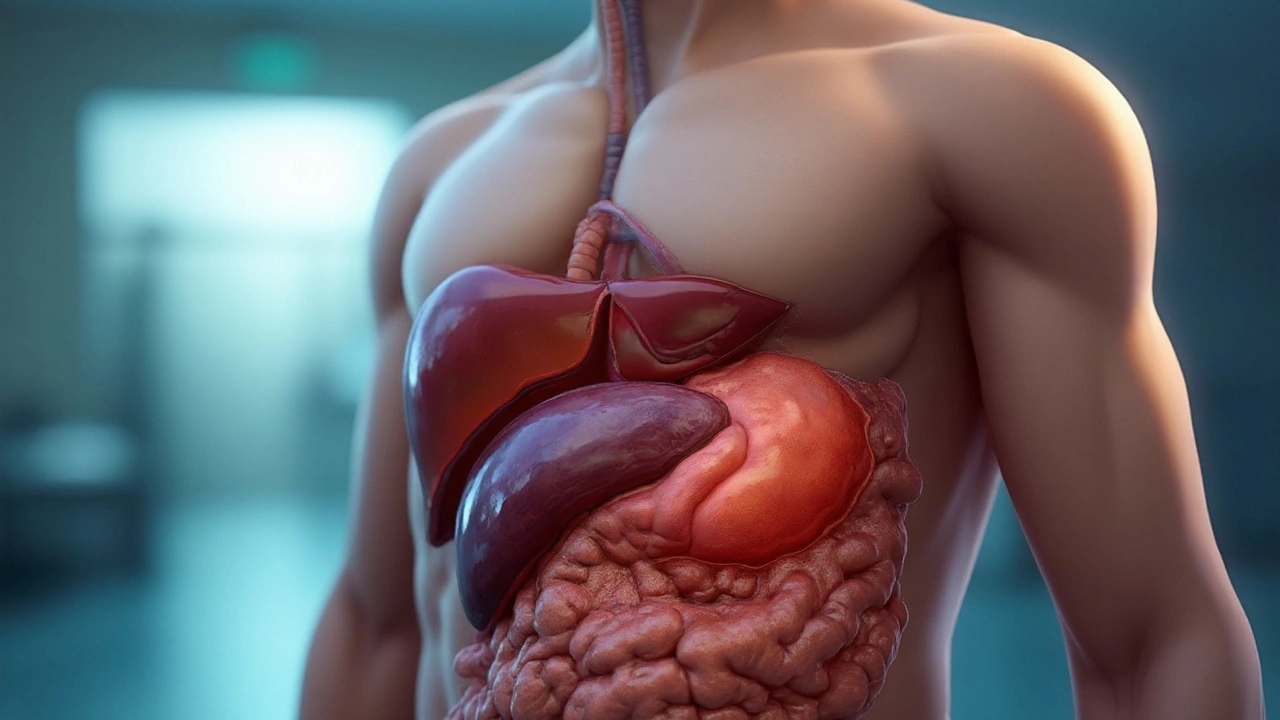

Hepatitis is a group of inflammatory liver conditions caused primarily by viral infections, alcohol, or metabolic disorders. When the inflammation becomes chronic, it can set the stage for liver cancer, specifically hepatocellular carcinoma. Understanding this chain helps patients and clinicians intervene early.

What is Hepatitis?

Hepatitis manifests as liver cell injury, leading to elevated enzymes and, in severe cases, scarring. The two viral culprits responsible for most cancer‑related cases are Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV). Both can persist for decades, quietly damaging DNA and triggering malignant transformation.

HBV vs. HCV: Key Differences

| Attribute | HBV | HCV |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission | Blood, sexual contact, perinatal | Bloodborne (IV drug use, unsafe medical practices) |

| Vaccine | Available, >95% efficacy | None |

| Chronic infection rate | ~5-10% of adults | ~75-85% of infected individuals |

| Liver cancer risk (per 100,000) | ~20-30 | ~10-15 |

| Current antiviral options | Tenofovir, Entecavir | Direct‑acting antivirals (DAAs) |

Both viruses integrate into liver cells, but HBV’s DNA can embed directly into the host genome, creating a permanent oncogenic stimulus. HCV, an RNA virus, triggers cancer mostly through chronic inflammation and oxidative stress.

How Chronic Hepatitis Leads to Liver Cancer

Three biological pathways connect prolonged hepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC):

- Persistent inflammation generates reactive oxygen species, damaging DNA.

- Regeneration cycles cause cellular proliferation, raising the chance of mutation.

- Fibrosis progresses to Cirrhosis, creating a fibrotic scaffold where malignant nodules can grow.

Clinicians often monitor the tumor marker Alpha‑fetoprotein (AFP). Elevated AFP, together with imaging, signals early HCC development.

Co‑Factors That Accelerate Cancer Development

Hepatitis doesn’t act alone. Lifestyle and metabolic issues amplify risk:

- Alcoholic liver disease: Heavy drinking doubles the chance of cirrhosis in HBV/HCV carriers.

- Non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Obesity‑related steatosis adds inflammatory stress.

- Smoking: Carcinogens travel through the bloodstream, worsening hepatic DNA damage.

When these factors converge, the timeline from infection to cancer shortens dramatically, sometimes within a decade.

Prevention: Vaccination, Antiviral Therapy, and Lifestyle

The most effective preventive tool is the HBV vaccine. Widespread neonatal immunization has already cut childhood liver‑cancer rates by more than 80% in high‑risk regions.

For those already infected, modern antivirals achieve viral suppression in >95% of patients:

- HBV: Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, Entecavir

- HCV: Sofosbuvir‑based direct‑acting antivirals (DAAs) with cure rates >99%

Clearing HCV eliminates the inflammatory driver, and sustained HBV suppression lowers the odds of cirrhosis and HCC. Pairing medication with reduced alcohol intake, weight management, and smoking cessation creates a triple‑shield against cancer.

Screening Strategies for High‑Risk Individuals

Guidelines from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) recommend six‑monthly ultrasound exams combined with AFP testing for anyone with chronic HBV/HCV and liver fibrosis stageF2 or higher.

When imaging detects a suspicious nodule, a liver biopsy confirms histology. Early‑stage HCC (≤3cm) can often be cured with surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation, or liver transplantation.

Managing a Liver Cancer Diagnosis

Once HCC is confirmed, treatment choice hinges on tumor size, liver function (Child‑Pugh score), and overall health. Options include:

- Surgical resection: Removes the tumor when liver reserve is adequate.

- Liver transplantation: Offers the best long‑term survival for patients meeting Milan criteria.

- Loco‑regional therapies: Trans‑arterial chemoembolization (TACE) or radio‑embolization for intermediate disease.

- Systemic therapy: Sorafenib, lenvatinib, or immunotherapy for advanced stages.

Post‑treatment surveillance mirrors the screening protocol-ultrasound and AFP every 3-6months-to catch recurrence early.

Putting It All Together: A Practical Checklist

- Know your hepatitis status: get tested for HBV and HCV if you haven’t.

- If positive, start antiviral therapy promptly.

- Vaccinate against HBV if you’re not already immune.

- Limit alcohol, maintain a healthy weight, and quit smoking.

- Enroll in semi‑annual ultrasound+AFP screening if you have chronic infection or cirrhosis.

- Stay informed about new treatment options; clinical trials often offer cutting‑edge therapies.

Following this roadmap cuts your liver‑cancer risk dramatically, turning a frightening statistic into a manageable health plan.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can hepatitis be cured?

HCV can be cured in >99% of cases with direct‑acting antivirals. HBV can be controlled but not eradicated; lifelong suppression is the goal.

How often should I get screened for liver cancer?

If you have chronic HBV/HCV with fibrosis≥F2, the recommendation is an ultrasound plus AFP every six months. Those with cirrhosis should follow the same schedule.

Is the HBV vaccine effective for adults?

Yes. A three‑dose series provides >95% protection in adults, and it’s especially beneficial for people at risk of exposure or who have chronic liver disease.

What role does AFP play in diagnosing liver cancer?

AFP is a serum marker that rises in many HCC cases. While a high AFP alone isn’t diagnostic, combined with imaging it improves early detection accuracy.

Does alcohol consumption increase cancer risk for hepatitis patients?

Absolutely. Alcohol accelerates fibrosis and doubles the odds of cirrhosis, which is the main gateway for hepatitis‑related HCC.

Are there lifestyle changes that can lower my liver‑cancer risk?

Yes. Adopt a balanced diet, exercise regularly, limit alcohol, quit smoking, and maintain a healthy weight. These steps reduce inflammation and improve liver resilience.

What treatment options exist for early‑stage HCC?

Curative options include surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation, and liver transplantation. Choice depends on tumor size, liver function, and overall health.

15 Comments