Antidepressant Tapering Calculator

Personalized Taper Plan

Calculate your safe tapering schedule based on the antidepressant you're taking.

Stopping an antidepressant isn’t as simple as missing a pill. Many people experience a cluster of uncomfortable (and sometimes scary) symptoms that show up within days of a dose change. This condition-known as antidepressant withdrawal-can be mistaken for a relapse, leading to confusion, unnecessary medication changes, and added distress. Below you’ll learn what the syndrome looks like, why it happens, which drugs are most likely to cause trouble, and how clinicians and patients can manage the process safely.

What is Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome?

Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome is a withdrawal condition that emerges after an antidepressant is reduced, switched, or stopped following at least one month of continuous use. The term was first introduced by Eli Lilly to separate these agents from drugs with higher addiction potential, but modern research treats the syndrome as a classic physiological withdrawal, not a psychological dependence.

How the Body Reacts: The Neuroadaptation Story

When you take an antidepressant daily, your brain adapts to the increased levels of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine. Over weeks or months the nervous system recalibrates-receptor densities shift, signaling pathways adjust, and downstream enzymes change their activity. If the drug is abruptly removed, the brain’s new “steady state” vanishes, leaving a temporary deficit that triggers the withdrawal symptoms documented in clinical guidelines.

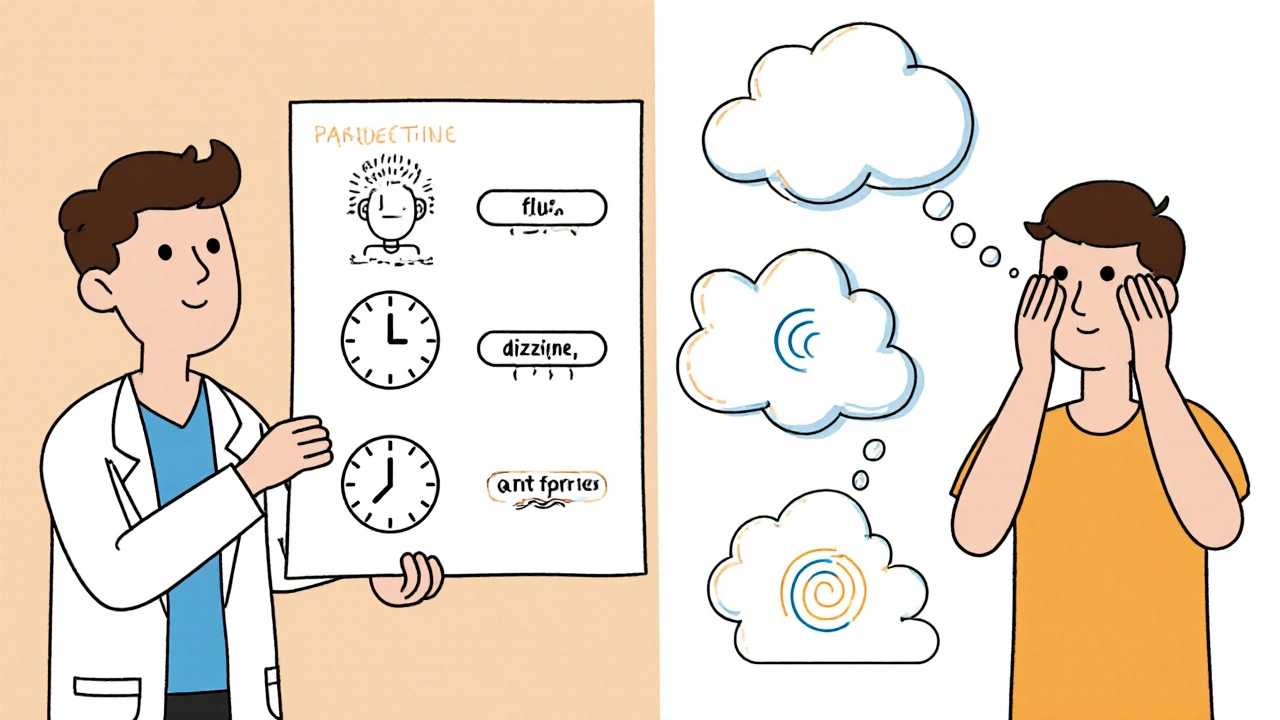

Common Symptoms - The FINISH Mnemonic

Clinicians often use the mnemonic FINISH to remember the most frequent complaints:

- Flu‑like symptoms - fatigue, muscle aches, headaches, feverish chills.

- Insomnia - difficulty falling asleep, vivid dreams, early awakenings.

- Nausea - queasy stomach, vomiting, loss of appetite.

- Imbalance - dizziness, vertigo, unsteady gait.

- Sensory disturbances - “brain zaps,” tingling, electric‑shock sensations.

- Hyperarousal - anxiety, irritability, restlessness (akathisia).

Surveys of patients on forums like Surviving Antidepressants and Reddit report these symptoms in roughly two‑thirds of cases, with brain‑zap sensations appearing in about 63 % of respondents.

Which Antidepressants Cause the Most Trouble?

Not all antidepressants are created equal when it comes to withdrawal risk. The key factor is the drug’s half‑life-how long it stays in the body after the last dose.

| Drug | Class | Half‑life (hours) | Typical withdrawal severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paroxetine | SSRI | 21 | High - intense brain‑zaps, nausea, insomnia |

| Venlafaxine | SNRI | 5‑11 | High - flu‑like symptoms, dizziness, emotional lability |

| Sertraline | SSRI | 26 | Moderate - nausea, headaches, occasional brain‑zaps |

| Fluoxetine | SSRI | 96‑120 (active metabolite) | Low - symptoms tend to be mild and delayed |

| Clomipramine | TCA | 19 | Moderate‑High - tremor, parkinsonism‑like stiffness |

| Phenelzine | MAOI | 11‑12 | Very high - agitation, psychosis, severe autonomic instability |

Short‑acting agents (paroxetine, venlafaxine, phenelzine) leave the bloodstream quickly, so the brain feels the drop sooner and more sharply. Long‑acting agents (fluoxetine) act like a built‑in taper, often smoothing out the withdrawal curve.

Class‑Specific Withdrawal Patterns

Understanding the typical profile for each drug class helps clinicians distinguish true relapse from withdrawal.

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) - frequent brain‑zaps, mild nausea, dizziness; paroxetine is the outlier with severe flu‑like symptoms.

- Serotonin‑Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) - similar to SSRIs but often more intense emotional swings and heightened blood pressure.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) - distinct motor issues such as tremor, stiffness, occasional parkinsonism‑like gait problems.

- Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) - the most severe spectrum, can provoke agitation, catatonia, or psychotic features demanding urgent psychiatric input.

Onset, Duration, and Protracted Cases

Symptoms usually appear within 2‑4 days after the last dose for short‑acting drugs, and up to a week for longer‑acting agents. Most people see a resolution in 1‑2 weeks, especially if the original medication is restarted. However, a growing body of patient‑reported data shows that 18‑28 % experience lingering effects beyond three months, and a small subset (roughly 5 %) report symptoms persisting for six months to a year.

Factors that prolong withdrawal include:

- High cumulative dose or many years of therapy.

- Rapid taper or abrupt stop.

- Co‑existing anxiety or mood disorders that amplify perception of physical discomfort.

- Pregnancy, where hormonal shifts can interact with neurotransmitter balance.

Distinguishing Withdrawal from Relapse

Relapse of depression or anxiety typically unfolds over several days to weeks and improves gradually when the drug is reinstated. In contrast, withdrawal appears suddenly, peaks within a few days, and often recedes within 72 hours of a modest “rescue” dose. Clinicians can use a simple test: give a low‑dose “catch‑up” of the original antidepressant; if symptoms abate quickly, they were likely withdrawal.

Prevention: Planning the Taper

The best way to avoid a painful break‑through is to taper methodically. Consensus guidelines recommend:

- Assess risk: Identify short‑half‑life agents, high doses, and any recent formulation switches.

- Choose a taper schedule: For SSRIs, a minimum of 4 weeks; for SNRIs like venlafaxine, at least 8 weeks; for MAOIs, 12 weeks with close monitoring.

- Use a longer‑acting bridge: Switch to fluoxetine or another long half‑life SSRI before tapering if the original drug is short‑acting.

- Reduce in small increments: Cut the dose by 10‑25 % every 1‑2 weeks, adjusting based on symptom load.

- Track symptoms daily: A simple diary helps the prescriber spot patterns and adjust the taper.

Studies show that a structured taper reduces severe withdrawal risk by roughly 62 % compared with abrupt cessation.

Managing Acute Withdrawal

If symptoms appear despite a taper, the following steps can help:

- Temporary dose increase: A modest “rescue” dose of the original medication often resolves symptoms within 24‑72 hours.

- Symptomatic support: NSAIDs for muscle aches, anti‑emetics for nausea, melatonin or short‑acting sleep aids for insomnia.

- Hydration and nutrition: Light meals, electrolyte drinks, and B‑vitamin complexes can ease flu‑like sensations.

- Psychological reassurance: Explain that symptoms are temporary and not a sign of relapse; mindfulness or light exercise can reduce anxiety.

For severe cases-especially with MAOI withdrawal-hospital admission and urgent psychiatric evaluation may be required.

Special Populations

Pregnant patients often wish to stop antidepressants due to fetal‑risk concerns. The AAFP notes that 41 % of pregnant women discontinue without medical guidance, increasing withdrawal risk. A joint decision with obstetric and psychiatric input is essential; a gradual switch to fluoxetine, which has a safer fetal profile, can be a viable option.

Elderly patients metabolize drugs slower, so even long‑acting agents may accumulate, leading to delayed withdrawal. Starting taper at half the usual decrement and monitoring renal function help avoid complications.

Key Takeaways for Patients and Clinicians

- Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is a physiological withdrawal, not a sign of addiction.

- Short‑half‑life drugs (paroxetine, venlafaxine, phenelzine) carry the highest risk.

- Symptoms follow the FINISH pattern and usually start within days of a dose change.

- A planned taper-4‑8 weeks for most agents-cuts severe withdrawal odds by more than half.

- If withdrawal occurs, a brief “rescue” dose often resolves symptoms quickly; seek professional help for protracted or severe cases.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does antidepressant withdrawal last?

Most people feel relief within 1‑2 weeks, but 18‑28 % report symptoms beyond three months and a minority can experience issues for six months or longer. Duration depends on drug half‑life, taper speed, and individual neurobiology.

Can I switch from a short‑acting SSRI to fluoxetine before tapering?

Yes. Switching to fluoxetine (half‑life 4‑6 days) creates a built‑in taper, allowing the brain to adjust more gradually. Clinicians usually overlap the two meds for 1‑2 weeks before initiating dose reductions.

What are “brain zaps” and are they dangerous?

Brain zaps are brief, electric‑shock‑like sensations often felt in the head or scalp. They’re uncomfortable but not harmful. They typically resolve when the drug is re‑introduced or the taper slows down.

Should I never stop my antidepressant on my own?

Never stop abruptly. Always discuss a discontinuation plan with a prescriber. Even a short, supervised taper can prevent severe withdrawal and reduce the chance of misdiagnosing a relapse.

Is there any medication that can help ease withdrawal symptoms?

There’s no specific antidote, but symptom‑directed treatments work: low‑dose benzodiazepines for severe anxiety, anti‑emetics for nausea, and over‑the‑counter analgesics for muscle aches. Always coordinate with your doctor before adding new meds.

Understanding antidepressant withdrawal empowers patients to make informed choices and helps clinicians avoid unnecessary medication changes. With a thoughtful taper and close monitoring, most people navigate the process safely and regain stability without a relapse.

9 Comments