For years, we’ve been told things like ‘you lose most of your body heat through your head’ or ‘chewing gum stays in your stomach for seven years.’ These ideas stick because they sound plausible, and we hear them from friends, family, or even well-meaning doctors. But when you look closer, many of these so-called facts are just stories dressed up as science. In patient education, these myths don’t just waste time-they can lead to real harm. Someone avoiding cold weather because they think their head is the main source of heat loss might not dress properly for winter. A parent who bans sugar to stop their child from ‘hyperactivity’ might miss the real cause of behavioral issues. The truth matters, especially when it comes to your health.

Myth: You Lose 70-80% of Your Body Heat Through Your Head

This one’s been around since the 1950s, probably because of a misinterpreted U.S. military study where soldiers were tested in arctic conditions wearing cold-weather gear-but no hats. Naturally, their heads lost the most heat because everything else was covered. But here’s the real math: your head makes up about 7 to 10% of your total body surface area. That means it loses roughly 7 to 10% of your body heat-not 80%. If you go outside barefoot in winter, your feet will lose just as much heat. If you wear a hat but leave your neck bare, you’ll still get cold. Heat loss depends on what’s exposed, not where it’s exposed. Wearing a hat helps, but it’s not a magic shield. Covering any uncovered part of your body-hands, neck, ears-will keep you warmer. This myth persists because it’s simple, and people want a quick fix. But understanding the real science helps you make smarter choices about staying warm.

Myth: You Need to Drink Eight Glasses of Water a Day

How many times have you heard this? ‘Drink eight glasses of water daily.’ It’s on fitness apps, in doctor’s offices, even on water bottles. But there’s no scientific basis for this number. Dr. Heinz Valtin, a kidney specialist at Dartmouth Medical School, reviewed over 100 peer-reviewed studies back in 2002 and found zero evidence supporting the ‘eight glasses’ rule. Your body gets water from food, coffee, tea, milk, and even fruits like watermelon. Hydration needs vary wildly based on your weight, activity level, climate, and health. A person working outdoors in Sydney in December might need 3 liters. Someone sitting at a desk in winter might need less than 1.5. The best indicator? Thirst. If you’re not thirsty and your urine is pale yellow, you’re likely hydrated. Chasing arbitrary water targets can lead to overhydration, which is dangerous. The ‘eight glasses’ myth is convenient-it’s easy to remember-but it’s not medicine. Listen to your body, not a slogan.

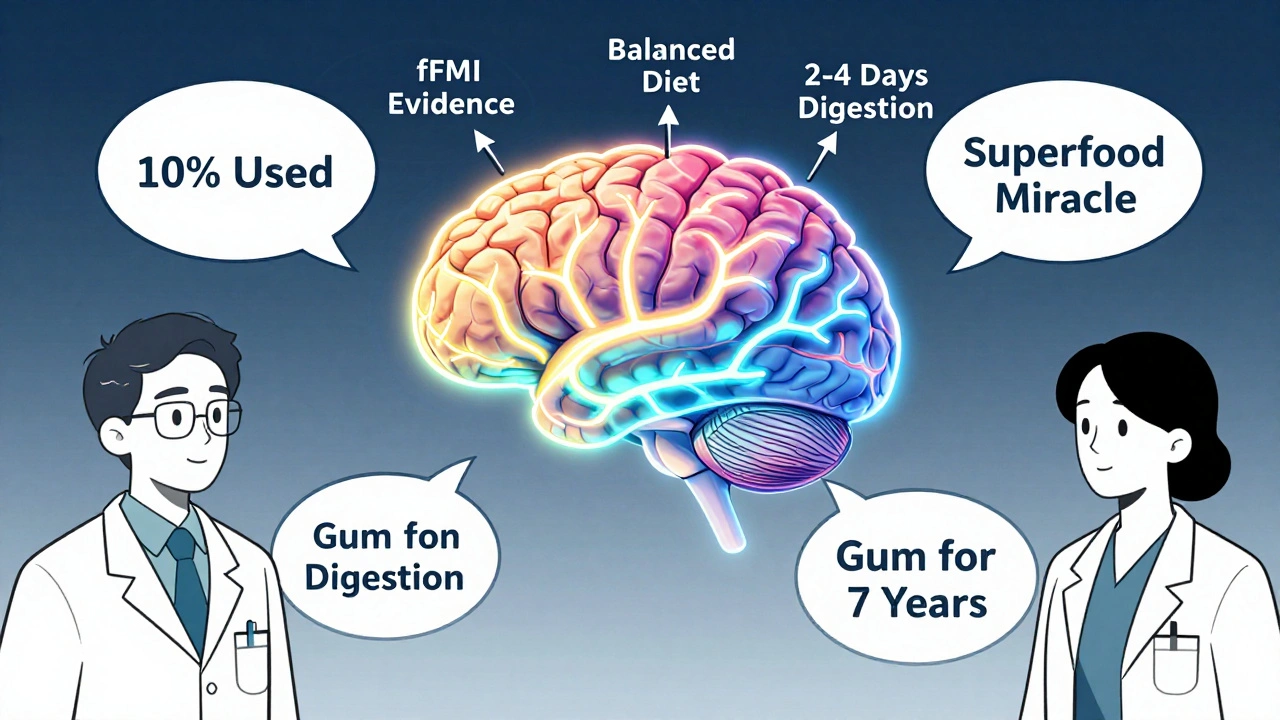

Myth: You Only Use 10% of Your Brain

This myth shows up in movies, ads, and self-help books promising you can unlock hidden potential. The truth? You use every part of your brain, all the time. Modern fMRI scans show activity across the entire brain-even during sleep. Different areas light up for different tasks, but no region is ever completely idle. The myth likely came from a misunderstanding of psychologist William James’ writings in the 1920s, which were later twisted by self-help gurus. Neuroscientists at the University of Alabama at Birmingham confirmed in 2022 that brain damage to even small areas can cause major impairments-something that wouldn’t happen if 90% of the brain were unused. If you only used 10%, losing a finger would be no big deal. But it’s not. Every part has a function. The brain doesn’t have unused storage space waiting to be tapped. It’s a highly efficient, always-on organ. Believing this myth leads people to chase pseudoscientific ‘brain boosters’ instead of focusing on proven methods like sleep, exercise, and mental stimulation.

Myth: Superfoods Like Acai or Goji Berries Are Miracle Cures

Walk into any health food store and you’ll see shelves lined with expensive ‘superfoods’ promising anti-aging, weight loss, or cancer prevention. But ‘superfood’ isn’t a scientific term-it’s a marketing label. Nutritional scientists at the European Food Information Council reviewed hundreds of studies and found no evidence that goji berries, acai, kale, or chia seeds offer health benefits beyond what you get from a balanced diet. A banana has just as much potassium as acai. Spinach has more iron than kale. The real difference? Price. A small bag of dried goji berries costs ten times more than an apple. You don’t need exotic imports to stay healthy. Eating a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins gives you everything your body needs. Spending extra on ‘superfoods’ doesn’t make you healthier-it just makes someone else richer. Focus on variety, not trends.

Myth: Chewing Gum Stays in Your Stomach for Seven Years

Parents have used this one to scare kids into spitting out gum since the 1950s. But your digestive system isn’t a trap. Chewing gum is made of synthetic rubber, sweeteners, and flavorings. Your body can’t digest the gum base, but it doesn’t stick around. It moves through your gut just like any other indigestible item-like corn kernels or seeds. Dr. Ian Tullberg, a family medicine specialist at UCHealth, confirmed in 2022 that gum passes through your system in two to four days. It doesn’t get stuck. It doesn’t wrap around your intestines. It’s not toxic. The only risk? Swallowing large amounts repeatedly, which could cause a blockage in young children. For adults, it’s harmless. This myth endures because it sounds gross and memorable. But the truth? Your body is built to handle things it can’t digest. You don’t need to panic every time you swallow gum.

Myth: Sugar Makes Kids Hyperactive

Every parent has seen it: a child eats candy at a birthday party, then runs around like a maniac. ‘Sugar did this,’ they say. But over 23 double-blind, controlled studies-including a major 2021 meta-analysis in JAMA Pediatrics-have found no link between sugar and hyperactivity. The real issue? Context. Birthday parties are exciting. Kids are surrounded by friends, loud music, and novelty. That’s what causes the energy surge, not the cake. Even more telling: when parents believe their child has consumed sugar (even when they haven’t), they report more hyperactive behavior. That’s expectation bias in action. The sugar myth survived for decades because it fits a cultural narrative. It’s easier to blame candy than to manage a child’s environment. Worse, the sugar industry spent millions in the 1990s to fund research that downplayed sugar’s real risks-like obesity and tooth decay-while pushing the hyperactivity myth as a distraction. Don’t cut sugar because you think it makes kids wild. Cut it because it’s bad for their teeth and long-term health.

Why Do These Myths Stick Around?

Not all myths are harmless. Some lead people to skip vaccines, avoid proven treatments, or waste money on fake cures. So why do they persist? Three reasons: simplicity, repetition, and emotion. Myths are easy to remember. ‘Eight glasses a day’ is clearer than ‘drink when thirsty.’ They’re repeated everywhere-on TV, in ads, by friends. And they tap into emotions: fear of illness, hope for quick fixes, guilt over parenting. A 2023 study from the University of Pennsylvania found that debunking myths can backfire if done poorly. Just saying ‘that’s false’ can make people cling harder to the lie, especially if it’s tied to their identity. The best way to correct a myth? Use the ‘truth sandwich.’ First, state the fact clearly. Then, briefly mention the myth-but label it as false. Finally, repeat the truth. For example: ‘Your brain uses 100% of its parts. Some people think you only use 10%, but that’s not true. Every part of your brain has a job, and scans show activity everywhere.’ This method increases retention by nearly 50%, according to the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

How to Spot a Myth Before You Believe It

Not every health claim is a myth-but many are. Here’s how to check before you accept something as true:

- Look for sources. Is it backed by peer-reviewed science? Or just a blog post or influencer?

- Check the date. Health advice changes. A 20-year-old ‘fact’ might be outdated.

- Ask: Who benefits? If a product is being sold, the claim might be designed to drive sales.

- Is it too simple? Real science is rarely black and white. If something sounds like a miracle cure, it probably isn’t.

- Search for expert consensus. One study doesn’t prove a rule. Look for what major medical organizations say.

When in doubt, ask your doctor. Not every question needs a Google search. Trusted health professionals can cut through the noise.

What’s Changing in Patient Education?

Hospitals and clinics are starting to take myth debunking seriously. In 2023, 68 U.S. hospitals added myth-busting sections to patient handouts-up from just 12 in 2020. The World Health Organization’s Myth Busters initiative has corrected over 2,300 health myths across 187 countries. Google now shows ‘About This Result’ boxes under search results, linking to fact-checks. These efforts work. A 2023 study showed patients who received myth corrections were 31% more likely to follow medical advice. But it’s not enough. We still rely too much on patients to find the truth themselves. The future of patient education isn’t just giving information-it’s actively correcting false beliefs before they take root. That means training doctors to spot myths during appointments, using clear visuals in clinics, and partnering with community leaders to spread accurate info. The goal isn’t to shame people for believing myths. It’s to give them better tools to think critically about their health.

Final Thought: Knowledge Is Power, But Only If It’s Accurate

Health myths aren’t just annoying-they’re dangerous when they lead people to ignore real risks or waste resources on fake solutions. The good news? We have the tools to fight them. Science, clear communication, and patient-centered education can replace myths with facts. You don’t need to be a scientist to spot a lie. You just need to ask: ‘Where’s the proof?’ and ‘Who says so?’ Start there, and you’ll be ahead of most people. Your health deserves better than stories. It deserves the truth.

Is it true that you lose most of your body heat through your head?

No. Your head makes up about 7-10% of your body’s surface area, so it loses roughly that percentage of heat when exposed. Heat loss depends on what’s uncovered, not where it is. Covering your head helps, but so does covering your hands, neck, or feet.

Do I really need to drink eight glasses of water every day?

No. There’s no scientific basis for this rule. Your water needs depend on your body size, activity level, climate, and diet. You get water from food, coffee, tea, and other drinks. Thirst and pale yellow urine are better guides than counting glasses.

Can chewing gum really stay in your stomach for seven years?

No. While your body can’t digest the gum base, it passes through your digestive system in two to four days, just like other indigestible items. It doesn’t stick around or cause blockages in healthy adults.

Does sugar cause children to become hyperactive?

No. Over 20 controlled studies have found no link between sugar and hyperactivity in children. The excitement often seen after eating candy comes from the event-like a party or celebration-not the sugar itself.

Are superfoods like acai or goji berries really better than regular fruits?

No. ‘Superfood’ is a marketing term, not a scientific one. Acai and goji berries have nutrients, but so do apples, bananas, and spinach. You don’t need expensive imports to get good nutrition. A balanced diet with varied fruits and vegetables is more effective-and cheaper.

Do we only use 10% of our brain?

No. Modern brain scans show activity across the entire brain, even during rest. Every part has a function. Damage to even small areas can cause serious effects, proving there’s no unused portion. This myth comes from a misinterpretation of old psychology studies.

What to Do Next

If you’ve been believing one of these myths, don’t feel bad. You’re not alone. These ideas are everywhere. The next step? Share the truth. Tell a friend about the body heat myth. Ask your doctor if a health claim you heard is real. Use trusted sources like the WHO, CDC, or your local hospital’s patient education materials. And when you see a sensational health claim online, pause. Ask: ‘Where’s the evidence?’ That small habit protects you-and others-from misinformation.

15 Comments