By the end of 2024, over 300 drugs were in short supply across the United States. Hospitals were scrambling. Oncology patients waited weeks for chemotherapy. Emergency rooms rationed life-saving antibiotics. Anesthetics vanished from operating rooms. This wasn’t a one-time crisis-it was the new normal. And the federal government, after years of reactive moves, finally launched a major overhaul in 2025. But is it enough?

What’s Really Causing Drug Shortages?

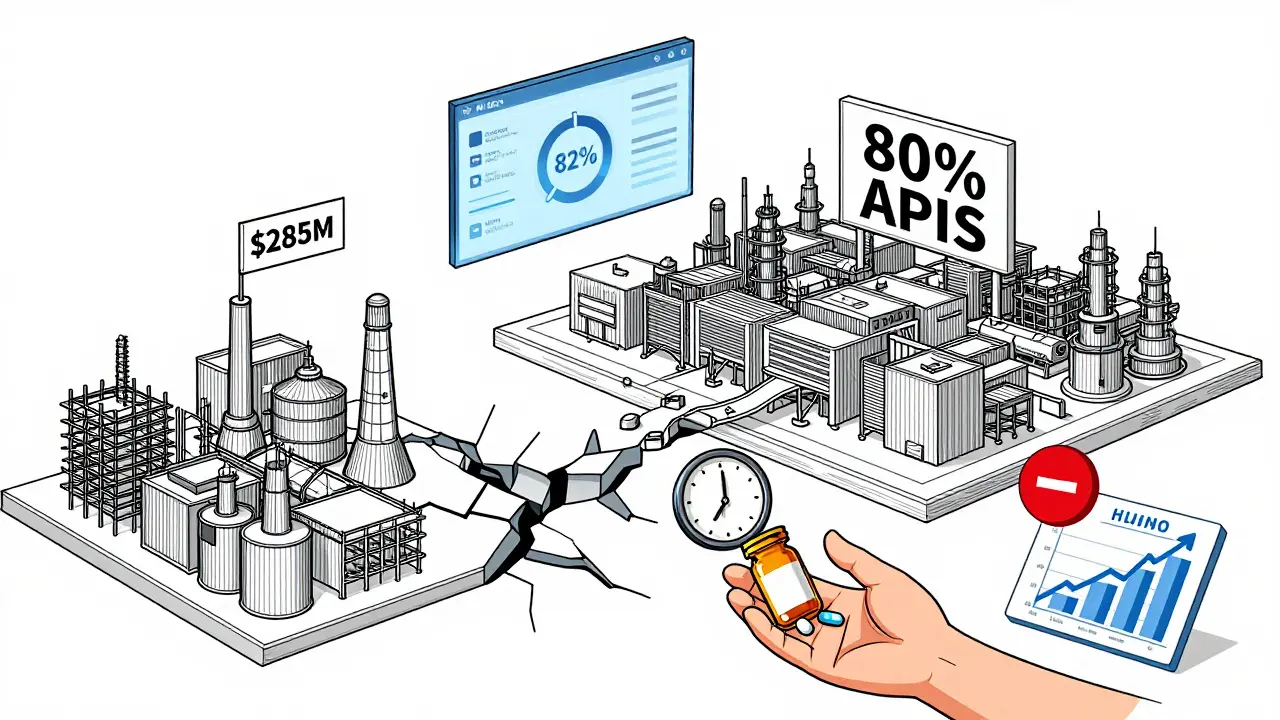

It’s not just bad luck or supply chain hiccups. The problem runs deep. Most critical drugs-especially sterile injectables like saline, insulin, and cancer meds-are made in just a handful of factories. Over 78% of these are produced in only five facilities nationwide. If one goes down, thousands of hospitals feel it. And most of those factories? They’re overseas. China supplies roughly 80% of the raw ingredients, called active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), used in U.S. medications. These APIs are cheap to make abroad, but they’re fragile. A single storm, political tension, or factory inspection delay can trigger a nationwide shortage. Even worse, making these drugs isn’t profitable. Companies lose money on low-margin essentials like antibiotics and painkillers. Why invest in backup production lines when you can make more money on pricier specialty drugs? The market doesn’t reward safety-it rewards profit. So when a factory shuts down or a shipment gets stuck, there’s no Plan B.The Federal Response: SAPIR and the 2025 Executive Order

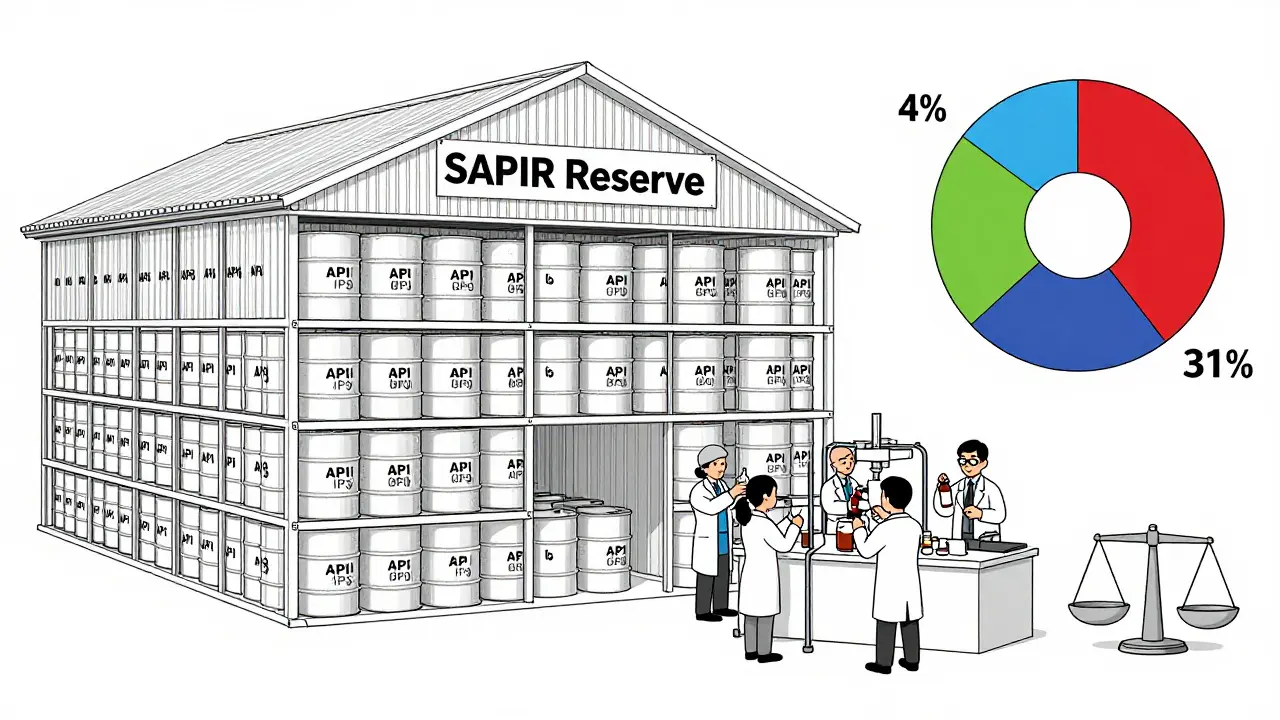

In August 2025, President Trump signed Executive Order 14178, which dramatically expanded the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve, or SAPIR. This program, first created in 2020, now stocks up on raw ingredients-not finished pills or injections-for 26 essential medicines. The logic? APIs last 3 to 5 years longer than finished drugs and cost 40-60% less to store. Instead of hoarding vials that expire, the government is stockpiling the building blocks. SAPIR targets antibiotics, anesthetics, and oncology drugs-the most critical and most frequently shorted. The idea is simple: if a factory fails, the U.S. can quickly turn stored APIs into medicine using domestic fill-finish facilities. It’s a shift from reacting to shortages to preparing for them. But here’s the catch: only 26 drugs. That’s less than 5% of all drugs that have ever gone short. The FDA’s own database shows over 1,200 drugs have had shortages since 2010. Oncology drugs alone make up 31% of all shortages-but only 4% of SAPIR’s list. Critics say it’s like building a fire station for one street while the whole neighborhood burns.Other Federal Moves: Reporting, Manufacturing, and Data

Beyond stockpiling, the federal government is trying to fix the system in other ways. The Department of Health and Human Services released its 2025-2028 Draft Action Plan with four goals: Coordinate, Assess, Respond, and Prevent. That means better communication between agencies, clearer data on where drugs come from, faster emergency responses, and incentives to make more drugs in the U.S. One key tool is the FDA’s Enhanced Shortage Monitoring System, launched in November 2025. It uses AI to track 17 data streams-shipping logs, factory output, hospital orders-and predicts shortages 90 days in advance with 82% accuracy. That’s huge. If a hospital knows a drug is coming short, they can order alternatives, adjust treatments, or even shift patients. Before this, most hospitals only found out when the shelves were empty. The FDA also started fast-tracking second-source manufacturers. In 2025, 14 companies applied to make versions of drugs that kept running out. If approved, these could add redundancy for eight high-risk medications by mid-2026. For the first time, the government is paying companies to compete-not just rely on one supplier. And there’s money. The Department of Commerce announced $285 million in CHIPS Act funding for new U.S. drug manufacturing plants. But experts say that’s less than 5% of what’s needed to truly fix the problem. Building a new API facility takes 5 to 7 years and costs over $100 million. The funding helps, but it’s a drop in the bucket.

Why the System Still Fails

Despite all this, the federal response is falling short in critical ways. First, reporting is broken. By law, manufacturers must tell the FDA six months before a shortage might happen. But only 58% actually do it. Small companies, especially those with under 50 employees, are 82% non-compliant. Without early warnings, the FDA can’t act in time. Second, enforcement is weak. Between 2020 and 2024, the FDA issued only 17 warning letters for missed reports. In the EU, under similar rules, they issued 142. No teeth means no accountability. Third, funding is shrinking. The 2026 HHS budget cut $1.2 billion from FEMA’s emergency response and $850 million from state public health grants. BARDA, the agency that funded breakthrough manufacturing tech, saw its budget drop 22%. Meanwhile, NIH’s drug development funding fell 18% in just one year. How can you innovate your way out of a crisis when you’re cutting the research that solves it? And then there’s the reality on the ground. Hospitals now spend an average of $1.2 million a year just managing shortages. Pharmacists work 10+ hours a week tracking down drugs. Nurses have to double-check every substitution. Patients skip doses because their meds aren’t there. In one case, a pharmacist had to compound cisplatin-cancer chemo-from raw powder because no finished product was available.How Other Countries Are Doing It Better

The European Union doesn’t wait for crises. They require member states to stockpile critical drugs and maintain real-time tracking through the European Medicines Agency. Between 2022 and 2024, their shortage rate dropped 37%. Why? Because they treat drug supply like public infrastructure-not a market commodity. They also approve new manufacturing facilities faster. In the U.S., it takes 28 to 36 months for FDA approval. In the EU, it’s 18 to 24 months. That difference means companies can respond quicker to demand. And they’re not waiting for a crisis to act.

What’s Working-and What’s Not

The FDA’s Early Notification Pilot Program showed real results. Hospitals that reported early saw shortages last 28% less time. That’s proof that transparency saves lives. But the current administration has weakened mandatory reporting rules. So while the AI system predicts shortages, it’s still flying blind on half the data. The SAPIR reserve is smart in theory. But it’s like buying a fire extinguisher for your kitchen and ignoring the gas leak in the basement. It helps with a few fires, but doesn’t fix the root cause: a broken economic model that punishes companies for making cheap, essential drugs. The most promising move? The push for second-source manufacturers. If two or three companies can make the same drug, one factory failure won’t shut down the country. But progress is slow. Only 14 applications are in the pipeline. That’s barely a start.The Bottom Line

The U.S. government is finally taking drug shortages seriously. But its actions are still patchwork. Stockpiling APIs helps in emergencies. AI predictions give hospitals a heads-up. Fast-tracking new makers could add backup supply. But none of it fixes the core problem: no one makes money on the drugs we need most. Until the government creates real financial incentives for producing low-margin essentials-through guaranteed contracts, price floors, or public manufacturing partnerships-shortages will keep coming. Stockpiles run out. Predictions get wrong. New factories take years. And patients? They’re still the ones who pay the price.What is the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve (SAPIR)?

SAPIR is a federal stockpile of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)-the raw chemical components of drugs-for 26 essential medicines like antibiotics, anesthetics, and cancer treatments. Created in 2020 and expanded in August 2025, it allows the U.S. to quickly produce finished drugs during shortages by using domestic manufacturing facilities. APIs are cheaper and last longer than finished drugs, making them more practical to store.

Why are drug shortages still happening despite federal efforts?

Because federal actions focus on symptoms, not causes. Stockpiling APIs and predicting shortages helps, but doesn’t fix the economic problem: manufacturers lose money on essential, low-cost drugs. With thin profit margins and no requirement to build backup capacity, companies avoid investing in redundancy. Only 58% of manufacturers report potential shortages, and only 12% of API production has been brought back to the U.S. despite years of effort.

How many drugs are currently in shortage in the U.S.?

As of late 2024, there were 277 active drug shortages, according to Global Biodefense. The FDA reported 98 active shortages at the end of 2024, but this number reflects only drugs they’ve officially confirmed. Different agencies use different counting methods, so the true number is likely closer to 250-300. Over 1,200 drugs have had shortages since 2010.

What’s the difference between SAPIR and the old drug stockpile approach?

Old stockpiles stored finished drugs-like vials of saline or antibiotics-which expire within 1-2 years and are expensive to replace. SAPIR stores the raw ingredients (APIs) used to make those drugs. APIs last 3-5 years longer and cost 40-60% less to store. This lets the U.S. respond faster and cheaper by producing drugs only when needed, rather than hoarding perishable products.

Can the U.S. really make more drugs domestically?

Yes, but it’s slow and expensive. Building a new API or drug manufacturing plant in the U.S. takes 5-7 years and costs over $100 million. The FDA approval process takes 28-36 months-much longer than the EU’s 18-24 months. While $285 million in CHIPS Act funding was announced in 2025, experts say $6 billion is needed to make a real difference. So far, 42% of new facilities approved in 2024 were still overseas.

How are hospitals affected by drug shortages?

Hospitals spend an average of $1.2 million per year managing shortages. Pharmacists work over 10 hours a week just tracking down drugs. 68% of facilities report treatment delays, and 42% report medication errors due to last-minute substitutions. In 2025, 89% of hospitals had to switch to alternative drugs, and 63% said those switches required extra monitoring. Some pharmacists even had to compound life-saving drugs from raw powder because nothing else was available.

16 Comments