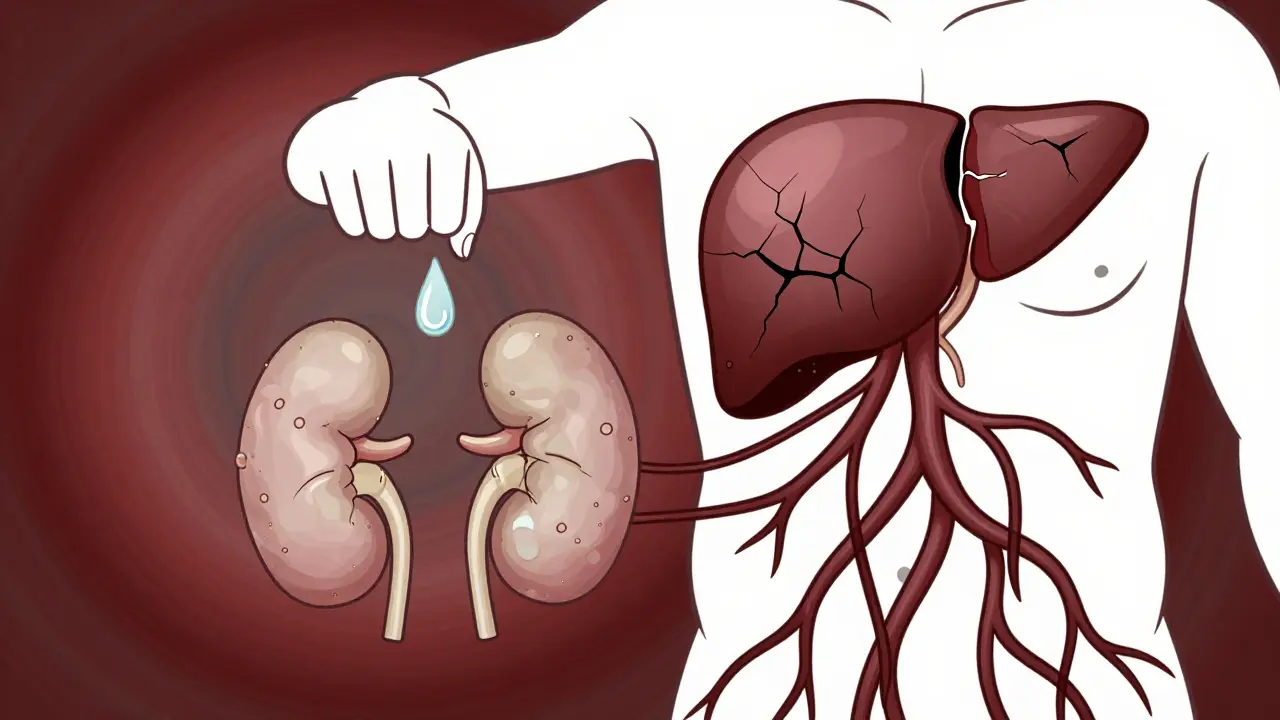

When your liver fails, it doesn’t just stop working - it starts pulling your whole body out of balance. One of the most dangerous ripple effects is hepatorenal syndrome, a condition where the kidneys shut down not because they’re damaged, but because the liver has already broken down too badly. This isn’t a normal kidney problem. It’s a medical emergency that happens in people with advanced cirrhosis, and it kills fast if no one acts.

Think of it like this: your liver is supposed to keep blood pressure steady in the abdominal area. When it’s destroyed by cirrhosis, blood vessels in the gut swell up, leaking fluid and dropping pressure in the main arteries. Your body thinks it’s going into shock. So it tightens every blood vessel it can - including the ones going to your kidneys. No blood flow means no urine output. The kidneys aren’t broken. They’re just starving.

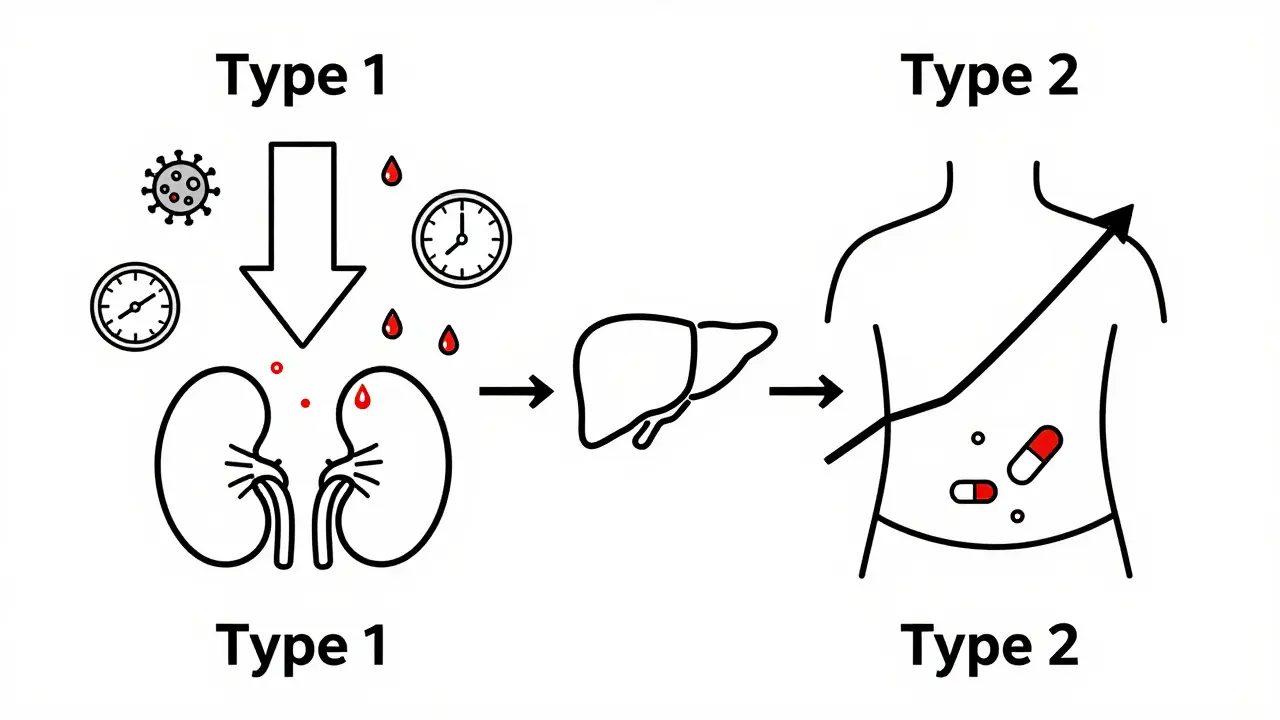

Two Types, Two Timelines

Hepatorenal syndrome doesn’t come in one flavor. There are two clear types, and they’re worlds apart in how fast they strike and how they’re treated.

Type 1 is the silent killer. It crashes over days. Creatinine - a waste product measured in blood tests - jumps from normal levels to over 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. That’s like going from a clean engine to one that’s seized. Median survival without treatment? Just two weeks. This type usually shows up after a trigger: an infection in the belly (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), heavy bleeding from the gut, or a sudden flare of alcohol-related liver damage. In fact, over one-third of Type 1 cases are linked to infection alone.

Type 2 moves slower. Creatinine climbs to between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL, and it sticks there. It’s tied to ascites - fluid building up in the belly - that won’t go away no matter how many diuretics you throw at it. People with Type 2 often live longer, but they’re stuck in a cycle: fluid builds up, kidneys struggle, the liver gets worse. It’s a slow burn, but it leads to the same place: transplant or death.

How Doctors Diagnose It (and Why They Often Get It Wrong)

You can’t diagnose hepatorenal syndrome with a scan or a biopsy. The kidneys look fine under the microscope. That’s the whole point. So doctors have to rule out everything else first.

Here’s what they check:

- Urine sodium under 10 mmol/L (your kidneys aren’t trying to get rid of salt)

- Urine osmolality higher than blood (your kidneys are still concentrating urine)

- No protein in urine or blood cells (no signs of kidney damage)

- No improvement after stopping diuretics and giving albumin (a protein that pulls fluid back into blood vessels)

And here’s the scary part: 25 to 30% of cases are misdiagnosed. A patient gets labeled as having “acute kidney injury” and gets treated with fluids or dialysis - both of which can make things worse. The real clue? If the creatinine drops after giving albumin and a vasoconstrictor, it’s HRS. If not, it’s something else.

Studies show that only 58% of non-specialist doctors can correctly identify HRS from a case description. That’s why many community hospitals miss it. You need someone who’s seen this before.

What Actually Works - And What Doesn’t

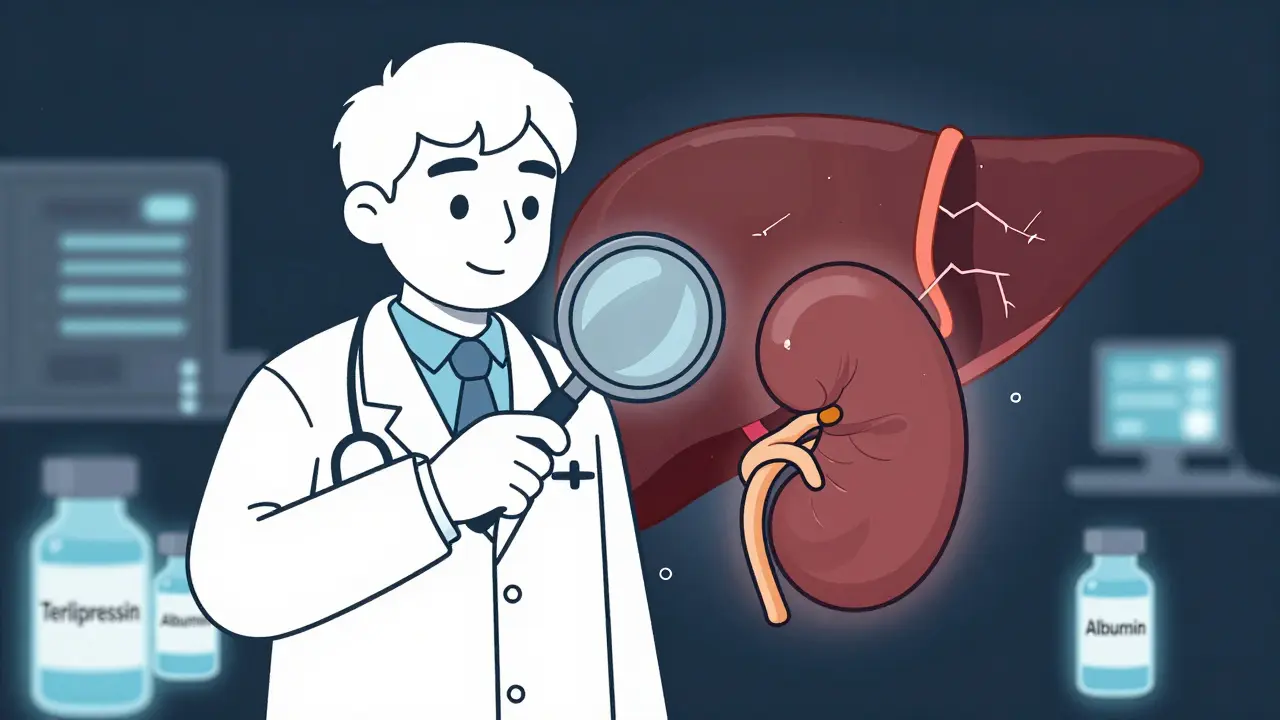

There’s no magic pill. But there are two real treatments that save lives.

The first is terlipressin - a drug that tightens blood vessels. It’s given intravenously every 4 to 6 hours, along with albumin infusions. In the CONFIRM trial, 44% of Type 1 patients saw their creatinine drop below 1.5 mg/dL within two weeks. That’s a big win. But it’s not easy. Side effects include stomach cramps, heart rhythm problems, and even heart attacks. One patient on Reddit described it: “My creatinine dropped from 3.8 to 1.9 in 10 days - but I was in so much pain I had to cut the dose in half.”

Terlipressin was approved in the U.S. in late 2022 under the brand name Terlivaz™. Each vial costs $1,100. A full 14-day course? Around $13,200. Insurance often fights it. Many patients still get compounded versions - cheaper, but less reliable.

For Type 2, some doctors try a procedure called TIPS - a shunt placed inside the liver to reroute blood flow. It works in 60 to 70% of cases. But it can trigger hepatic encephalopathy - brain fog, confusion, even coma - in up to 30% of patients. It’s a trade-off: better kidneys, worse brain.

Other drugs like midodrine and octreotide are used off-label. They’re cheaper, but less effective. One patient on a liver disease forum said: “We tried midodrine for six weeks. Nothing changed. We got on the transplant list.”

The Only Real Cure

No matter how well you treat it, hepatorenal syndrome won’t go away unless the liver is replaced.

Liver transplant is the only permanent fix. Data from the United Network for Organ Sharing shows:

- With vasoconstrictors + albumin: 38.7% survive one year

- With just supportive care: 18.2% survive one year

- After transplant: 71.3% survive one year

That’s why experts now recommend listing all Type 1 patients for transplant immediately - even if their creatinine doesn’t improve with treatment. One 2022 study found patients who got transplanted within 30 days had a 68.4% survival rate. Those who didn’t? Only 22.1%.

And here’s a recent change: the MELD-Na score - the system used to rank who gets a liver next - now gives extra points for kidney failure. If you have HRS, you jump up the list. That’s a big deal. It means you’re not just a liver patient anymore. You’re a liver-and-kidney patient. And that changes everything.

What’s on the Horizon

Researchers are chasing better ways to catch HRS before it hits. One promising tool is a urine biomarker called NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin). Early data suggests it can predict HRS days before creatinine rises. The PROGRESS-HRS trial is testing if NGAL above 0.8 ng/mL can flag high-risk patients early enough to intervene.

Other drugs are in trials - new vasopressin agonists, ammonia-reducing agents, even wearable pumps to drain ascites. But none have broken through yet. The biggest barrier isn’t science - it’s access. In North America, 63% of HRS patients get vasoconstrictors. In sub-Saharan Africa? Only 11%. Most get nothing but fluids and hope.

What You Need to Know

If you or someone you care about has cirrhosis and suddenly stops peeing, or swelling gets worse despite diuretics - don’t wait. Go to a liver specialist. Ask: “Could this be hepatorenal syndrome?”

Key signs to watch:

- Urine output drops below 500 mL per day

- Swelling in legs or belly gets worse fast

- Confusion or drowsiness starts

- Cramps or chest pain after starting new meds

Don’t let misdiagnosis delay care. Ask for albumin infusion and terlipressin if Type 1 is suspected. Push for transplant evaluation - even if you’re not “sick enough” by old standards.

Hepatorenal syndrome is not a death sentence. But it’s a race. And the clock starts the moment the liver fails.

Can hepatorenal syndrome be reversed without a transplant?

In some cases, yes - especially Type 2. Medications like terlipressin and albumin can restore kidney function in about 40% of Type 1 cases and up to 70% of Type 2 cases when combined with TIPS. But these are temporary fixes. Without a transplant, the liver continues to fail, and HRS almost always returns. The only long-term reversal is liver transplantation.

Is hepatorenal syndrome the same as kidney failure from diabetes or high blood pressure?

No. Diabetes and high blood pressure cause structural damage to the kidneys - scarring, clogged vessels, worn-out filters. HRS is different. The kidneys are structurally normal. They fail because blood flow is cut off due to liver disease. It’s a functional problem, not a physical one. That’s why dialysis often doesn’t help - the issue isn’t the kidneys, it’s the liver.

Why is terlipressin not available everywhere?

Terlipressin is FDA-approved in the U.S. since 2022, but it’s expensive - over $13,000 for a two-week course. Many insurers deny coverage, and it’s not approved in many countries. In low-income regions, it’s rarely available. Even in the U.S., only 35% of hospitals have formal protocols for using it. Most patients still get off-label alternatives like midodrine and octreotide, which are cheaper but less effective.

Can alcohol use make hepatorenal syndrome worse?

Yes. Continuing to drink after cirrhosis diagnosis dramatically increases the risk of HRS. Alcohol directly worsens liver damage and triggers inflammation that leads to splanchnic vasodilation - the first step in HRS. In fact, 11% of Type 1 cases are triggered by acute alcoholic hepatitis. Stopping alcohol is not optional - it’s the first step in any treatment plan.

How do I know if I’m at risk for hepatorenal syndrome?

You’re at risk if you have cirrhosis - especially with ascites, high MELD-Na score, recent infection, or GI bleeding. People over 55 are more commonly affected. If you’ve been told your liver is “end-stage,” you should be screened regularly for kidney function. Ask your doctor to check your serum creatinine and urine sodium every 3 to 6 months. Early detection is what saves lives.

13 Comments