When you take a pill once a day instead of three times, it’s not magic-it’s science. Modified-release (MR) formulations are engineered to control how and when a drug enters your bloodstream. They’re designed to keep drug levels steady, reduce side effects, and make life easier for people managing chronic conditions. But here’s the catch: just because two pills look the same doesn’t mean they work the same. For generic versions of these drugs, proving they’re equivalent to the brand-name product isn’t as simple as comparing blood levels at one point in time. That’s where bioequivalence gets complicated.

Why Modified-Release Formulations Are Different

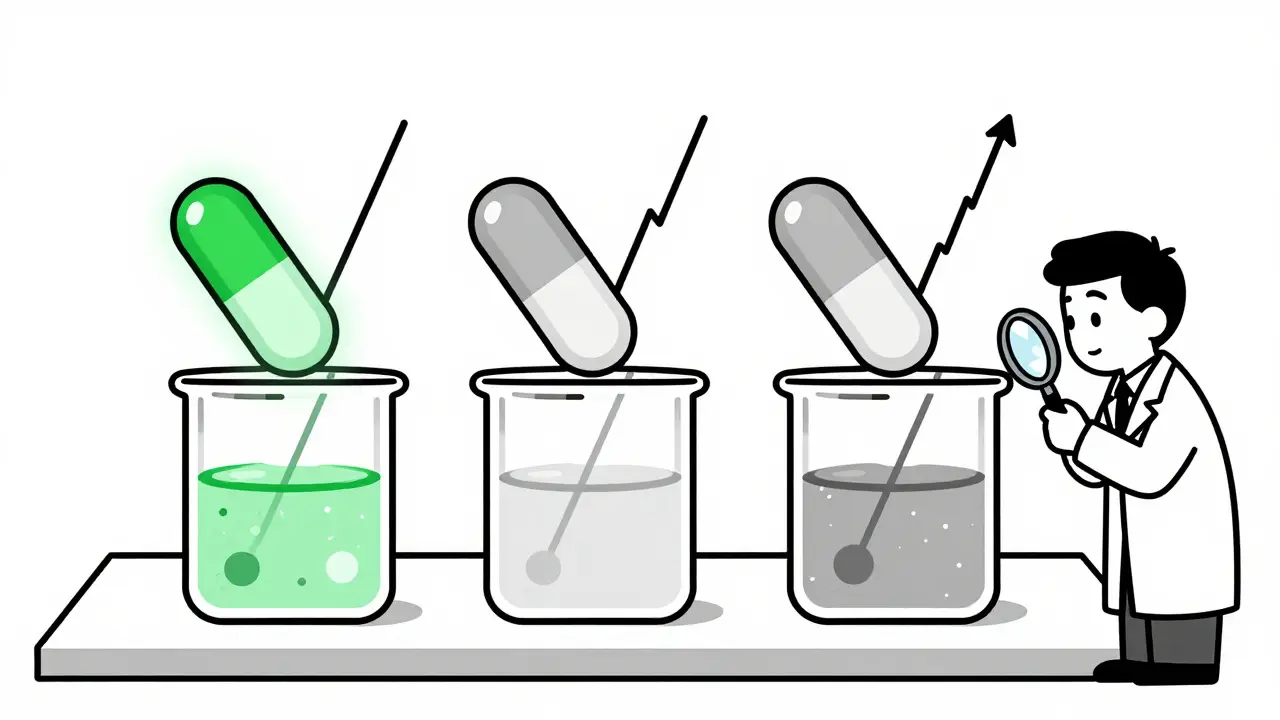

Immediate-release pills dump their entire dose into your system within an hour. Modified-release versions-like extended-release (ER), delayed-release, or multiphasic tablets-release the drug slowly, in bursts, or at specific locations in the gut. Think of it like a slow-burn candle versus a match. The goal is to avoid spikes and crashes in drug concentration, which can mean fewer side effects and better control of conditions like high blood pressure, epilepsy, or ADHD. But this complexity makes it harder to prove a generic version works just as well. With immediate-release drugs, you check the peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) and call it done. For MR drugs, those two numbers alone aren’t enough. You need to know how the drug behaves over time. Did the first 2 hours match? What about the next 8? If the early release is too fast, you risk toxicity. Too slow, and the drug won’t work when it’s needed.How Regulators Measure Bioequivalence for MR Drugs

The FDA, EMA, and WHO all agree that bioequivalence matters-but they don’t all agree on how to measure it. The FDA’s 2022 guidance is the most detailed. For most extended-release products, they require a single-dose, fasting study. Why? Because multiple-dose studies can get messy. Drug accumulation, patient compliance, and metabolism changes over time can mask real differences between products. For drugs with multiple release phases-like Ambien CR, which gives you a quick sleep onset followed by sustained sleep maintenance-the FDA demands partial AUC measurements. That means they look at the area under the curve from 0 to 1.5 hours (the fast-release part) and from 1.5 hours to infinity (the slow-release part). Both must fall within the 80-125% range. If one part fails, the whole product fails. The EMA takes a different approach. They sometimes require steady-state studies, especially if the drug builds up in the body over time. They also focus on metrics like half-value duration and midpoint duration time, which measure how long the drug stays active. It’s not that one is right and the other wrong-it’s that they prioritize different risks.The Dissolution Test: More Than Just a Lab Experiment

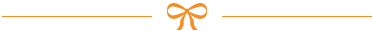

Dissolution testing is where most generic drug developers get stuck. You can’t just test one pH level. The FDA requires testing at pH 1.2 (stomach), 4.5 (upper intestine), and 6.8 (lower intestine). Why? Because a tablet might dissolve perfectly in the lab’s buffer solution but fail in real life when it hits acidic stomach fluid or alkaline intestines. A formulation scientist at Teva reported that 35-40% of early ER oxycodone generic attempts failed because the dissolution profile didn’t match across all three pH levels. The same issue happens with drugs like dextroamphetamine sulfate ER, where USP Apparatus 3 or 4 (oscillating baskets or flow-through cells) are needed instead of the standard paddle method. These aren’t just technical details-they’re make-or-break steps. Even more, if a drug contains 250 mg or more of active ingredient, it must pass an alcohol dose-dumping test. Alcohol can cause the tablet to release all its contents at once-potentially leading to overdose. Between 2005 and 2015, seven ER products were pulled from the market because of this exact issue.

When the Numbers Aren’t Enough: Highly Variable and Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Some drugs are naturally unpredictable in the body. Their blood levels vary wildly from person to person. These are called highly variable drugs (HVDs). For these, the standard 80-125% bioequivalence window is too loose. The FDA uses Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE) to adjust the range based on how variable the reference product is. The upper limit can stretch to 57.38% under certain conditions, but this requires complex statistical modeling and more participants-adding 6 to 8 months to development time. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or some antiepileptics-the stakes are even higher. A small difference in absorption can mean a seizure or a dangerous bleed. The FDA requires tighter limits: 90.00-111.11%. And you must prove that both the test and reference products have similar within-subject variability. Many generics fail here because they assume bioequivalence is just about averages. It’s not. It’s about consistency.Why Some Generics Still Fail-Even When They Pass the Tests

In 2012, a generic version of Concerta (methylphenidate ER) was rejected because it didn’t match the reference product’s early release profile. The FDA’s Complete Response Letter pointed out that the generic released too little drug in the first 2 hours. Patients reported reduced effectiveness. The product passed standard AUC and Cmax tests-but failed the critical early phase. That’s why partial AUCs matter. Even more troubling, a 2016 study in Neurology found that 18% of generic MR antiepileptic drugs had higher seizure breakthrough rates than the brand, even though they passed all regulatory bioequivalence tests. This suggests that current standards might not capture all clinical risks. The system is designed to prevent major differences-but minor ones can still hurt patients.

Cost, Time, and Who Can Afford to Play

Developing a generic MR drug isn’t cheap. It costs $5-7 million more than an immediate-release version. A single-dose MR bioequivalence study runs $1.2-1.8 million. That’s compared to $0.8-1.2 million for IR. Only large companies or big contract research organizations (CROs) like PRA Health Sciences, ICON, or Syneos Health can afford it. Small biotechs? They’re out. That’s why 97% of MR generic applications come from big players. The learning curve is steep too. Pharmacokinetic scientists need 12-18 months of specialized training to handle dissolution modeling, RSABE statistics, and IVIVC (in vitro-in vivo correlation) analysis. Many applicants fail their first submission because they don’t understand the nuances of pH testing or partial AUC timing.What’s Next for Modified-Release Bioequivalence?

The FDA is working on a new 2024 guidance for complex MR products-things like gastroretentive systems and multiparticulate beads. The EMA is also moving toward aligning with the FDA, possibly dropping the steady-state requirement for most products. That could simplify things globally. Meanwhile, companies are turning to mechanistic modeling-like PBPK (physiologically based pharmacokinetic) models-to predict how a drug will behave in the body before running expensive human trials. Over two-thirds of major pharma companies now use these tools. It’s not science fiction-it’s becoming standard practice. The bottom line? Modified-release formulations are here to stay. They’re the future of chronic disease management. But making sure generics are truly equivalent requires more than just matching pill shapes and active ingredients. It demands precision, patience, and a deep understanding of how drugs move through the body-not just in theory, but in real people, under real conditions.Why can’t we just use the same bioequivalence rules for modified-release and immediate-release drugs?

Because modified-release drugs are designed to release the active ingredient over hours, not all at once. A single blood sample taken at peak time won’t show if the drug is being released too fast, too slow, or unevenly. For immediate-release drugs, Cmax and AUC are enough. For modified-release, you need to see the full release profile-especially early and late phases-using partial AUC measurements and dissolution testing across multiple pH levels.

What’s the biggest reason generic modified-release drugs get rejected?

The most common reason is failure to match the dissolution profile across all required pH levels-especially pH 1.2, 4.5, and 6.8. Many generics work fine in the lab’s buffer solution but fail when tested under conditions that mimic the stomach and intestines. Another major reason is inadequate partial AUC data for multiphasic products, like those with both immediate and extended-release components.

Does alcohol really affect modified-release pills?

Yes, and it’s a serious safety issue. Alcohol can cause some extended-release tablets to release their entire dose at once-a phenomenon called "dose dumping." This can lead to dangerous spikes in drug levels. The FDA requires alcohol testing for any ER product containing 250 mg or more of active ingredient. Between 2005 and 2015, seven such products were withdrawn from the market because of this risk.

Why do some generic MR drugs still cause seizures even if they pass bioequivalence tests?

Standard bioequivalence tests look at average blood levels, but they don’t always capture subtle differences in release timing or consistency. For drugs like antiepileptics, even a small delay in absorption or a slight drop in concentration can trigger a seizure. A 2016 study found that 18% of generic MR antiepileptic drugs had higher breakthrough seizure rates than the brand, despite meeting FDA bioequivalence criteria. This shows that current standards may not be enough for drugs with a narrow therapeutic window.

Is a generic modified-release drug always cheaper than the brand?

Not always. While generics are usually cheaper, the development cost for an MR generic is $5-7 million higher than for an immediate-release version. That cost gets passed on. Some MR generics cost nearly as much as the brand, especially for complex products like extended-release stimulants or cardiac medications. The savings come from competition over time-not from lower development costs.

Can I trust a generic modified-release drug?

Most can. The vast majority of approved MR generics are safe and effective. Regulatory agencies like the FDA have strict, science-based standards. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or certain seizure medications-some patients and doctors prefer to stick with the brand. If you notice changes in how you feel after switching, talk to your doctor. It’s not always the drug-it might be your body’s sensitivity to small differences in release patterns.

11 Comments