By 2025, more than one in five Americans are over 65. That’s 73 million people - and many of them struggle to understand their own health information. It’s not because they’re not smart. It’s because most medical materials aren’t made for them.

Why standard health materials fail older adults

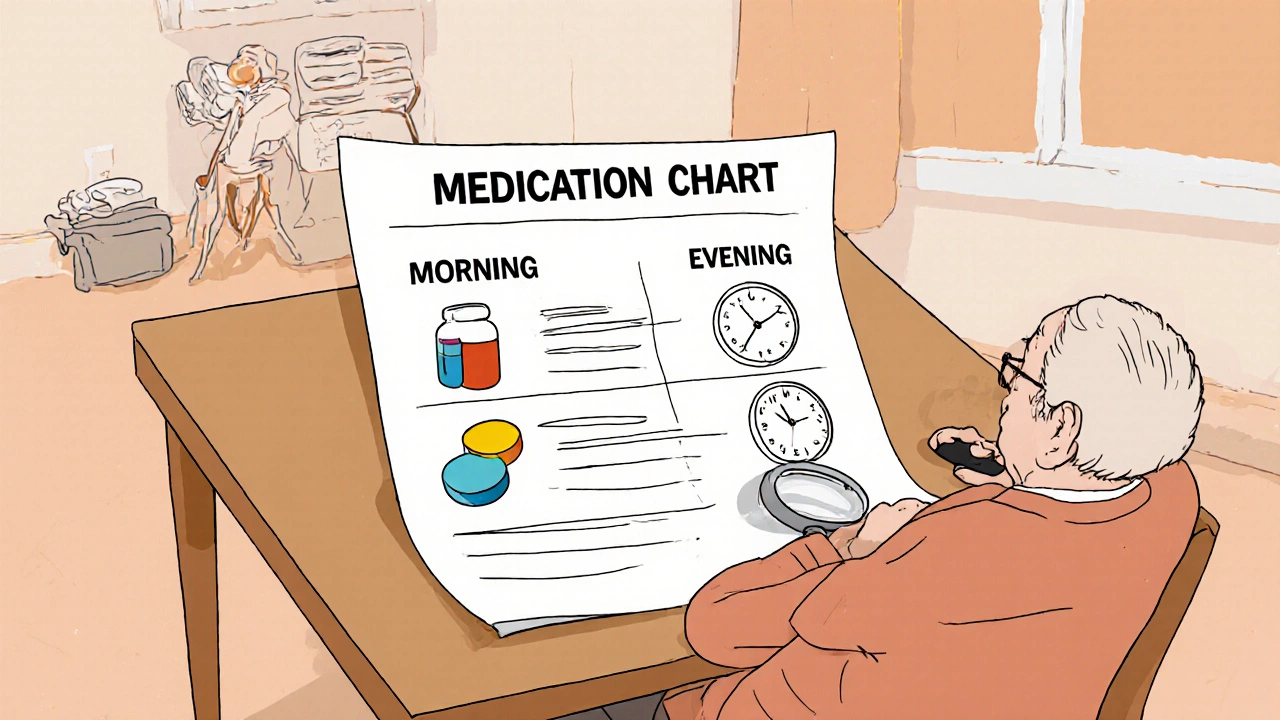

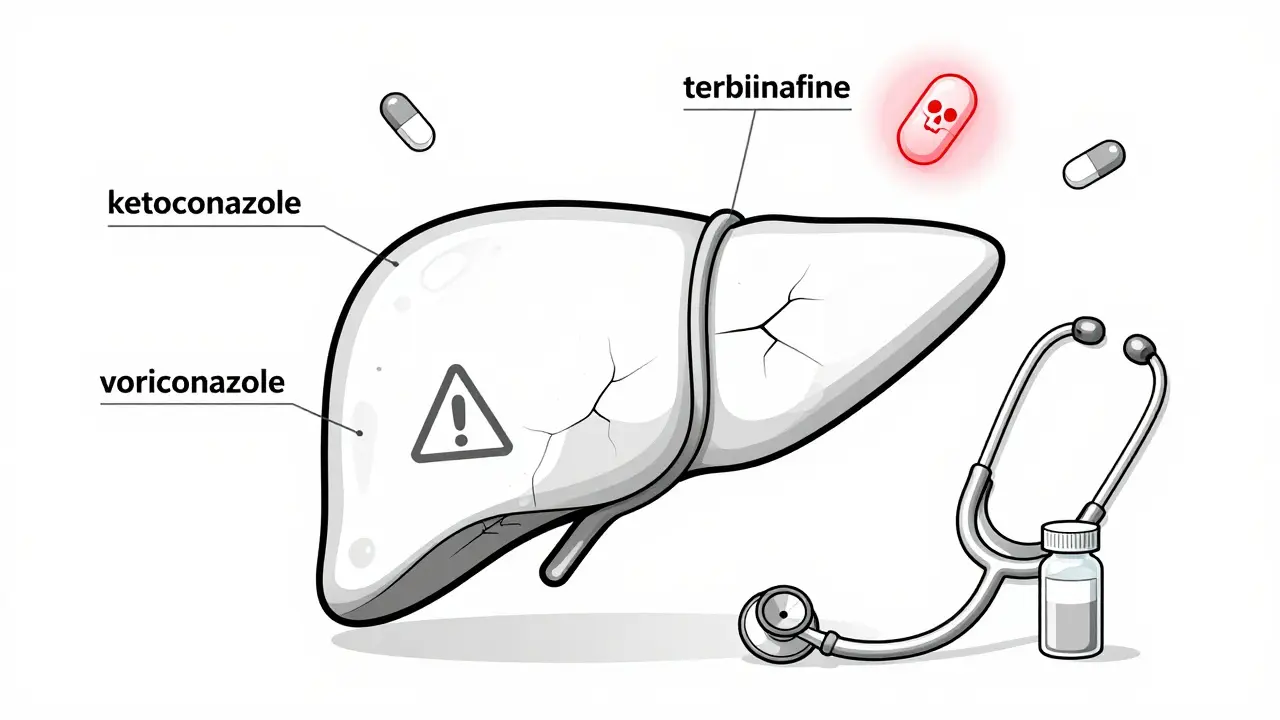

A 2023 CDC report found that 68% of adults over 60 have trouble reading medication labels, understanding doctor’s notes, or filling out insurance forms. Even simple things like ‘take twice daily’ or ‘avoid grapefruit’ get lost. Why? Most brochures are written at a 9th-grade reading level. The average senior reads at a 5th-grade level. That’s a huge gap. It’s not just about words. Older eyes need bigger fonts. Many seniors have trouble seeing fine print, especially under dim lighting. Arthritis makes holding small papers hard. Memory issues mean they forget instructions after leaving the clinic. And fear of looking stupid? That keeps many from asking for help. One caregiver in Ohio told me her 78-year-old husband took his blood pressure pill at night instead of morning - because the label said ‘take once a day’ and he assumed that meant ‘at bedtime.’ He didn’t know what ‘daily’ meant in a medical context. That’s not his fault. That’s a system failure.What makes good senior patient education materials

Effective materials for older adults follow clear, proven rules - not guesswork. The National Institute on Aging and the American Geriatrics Society agree on the basics:- Font size: 14-point or larger - no exceptions. Times New Roman or Arial are best. Avoid fancy fonts.

- High contrast - black text on white paper. No light gray on beige.

- Simple language - write at a 3rd to 5th-grade level. Use short sentences. No jargon. Say ‘take your medicine’ instead of ‘administer the prescribed pharmacological agent.’

- One idea per page - don’t overload. One handout for blood pressure, another for diabetes, another for walking safely.

- Use pictures - a drawing of a pill bottle with an arrow pointing to ‘morning’ and ‘evening’ works better than text.

- Include a ‘teach-back’ prompt - a simple line like: ‘Can you tell me how you’ll take this medicine?’ helps confirm understanding.

Where to find trusted, ready-to-use materials

You don’t have to create everything from scratch. These are free, trusted sources used by clinics, hospitals, and senior centers across the U.S.:- HealthinAging.org - run by the American Geriatrics Society. Over 200 easy-to-read guides on topics like falls, memory, and managing multiple medications. All reviewed by doctors and tested with seniors.

- MedlinePlus Easy-to-Read - the National Library of Medicine’s collection. 217 resources, alphabetized by topic. Search ‘diabetes’ or ‘heart failure’ and pick the ‘Easy-to-Read’ version.

- National Institute on Aging (NIA) - their ‘Talking With Your Older Patients’ guide is a gold standard. Also has free printables on exercise, nutrition, and brain health.

- CDC Healthy Aging - offers downloadable fact sheets on flu shots, vaccines, and chronic disease management. All follow universal health literacy standards.

How to use these materials in real life

Giving a senior a handout isn’t enough. Here’s how to make sure it actually helps:- Read it together - sit down, not just hand it over. Say, ‘Let’s look at this together.’

- Use the ‘teach-back’ method - after explaining, ask: ‘Can you show me how you’d take this pill?’ or ‘What would you do if you felt dizzy?’

- Check the environment - is the room bright? Can they see the paper? Is there a magnifying glass nearby?

- Repeat key points - don’t assume they got it the first time. Say it again, differently.

- Let them keep it - give them a copy. Put it on the fridge. Tape it to the medicine cabinet.

What’s new in senior education tools

Technology is helping - but only if it’s designed right. Telehealth use among seniors jumped from 17% in 2019 to 68% in 2023. But many video apps are too complex. That’s why the NIA updated its Go4Life program in early 2024 with voice-guided exercise videos. You just say, ‘Play my morning stretch,’ and it starts. HealthinAging.org added 47 new resources in 2023, including ones for people with early memory loss. One guide uses photos of real people’s medicine cabinets to show how to organize pills by day and time. The NIH is now funding a $4.2 million project to build AI tools that adjust content based on how someone responds. If a senior pauses a lot on a question about blood sugar, the system might switch to pictures or simplify the language - all in real time.Why this matters - and why it’s still not happening enough

Poor health literacy costs the U.S. system between $106 billion and $238 billion a year. Seniors with low health literacy are 2.3 times more likely to report poor health. They’re 1.7 times more likely to have diabetes. And they’re more likely to end up back in the hospital. Hospitals that use these materials see 14.3% fewer readmissions. That’s $1,842 saved per patient. Yet, a 2023 survey found only 28% of U.S. clinics have fully adopted these practices. Why? Staff are stretched thin. Budgets are tight. Many providers never learned how to communicate with older patients. But change is coming. The American Medical Association now requires all medical students to get 8 hours of health literacy training by 2026. Medicare is pushing hospitals to track health literacy outcomes. And Congress is increasing funding for senior education programs from $187 million in 2023 to $312 million by 2027.What you can do today

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Here’s how:- Ask for easy-to-read materials - if your doctor gives you a thick pamphlet, say: ‘Can I get a simpler version?’

- Use a magnifying glass - keep one by the medicine cabinet.

- Write it down - if you’re told to take a pill ‘before meals,’ write ‘before breakfast, lunch, dinner’ on the bottle.

- Bring someone with you - a family member or friend can help remember what the doctor said.

- Use free resources - visit HealthinAging.org or MedlinePlus. Print out what you need.

What reading level should senior patient education materials be written at?

Senior patient education materials should be written at a 3rd to 5th-grade reading level. This matches the average reading ability of many older adults, especially those with limited health literacy. Even though the national average is around 7th to 8th grade, most seniors benefit from simpler language, short sentences, and clear visuals. Research shows materials at this level improve understanding by up to 42% compared to standard medical text.

What font size is recommended for older adults?

The recommended minimum font size is 14-point. Many seniors have vision changes due to aging, so larger fonts help them read without strain. Avoid small fonts like 10 or 11-point, even if they look neater. Use clear, sans-serif fonts like Arial or Helvetica. High contrast - black text on white paper - is just as important as size.

Are there free resources for senior health materials?

Yes. Trusted, free resources include HealthinAging.org (by the American Geriatrics Society), MedlinePlus Easy-to-Read (from the National Library of Medicine), and the National Institute on Aging’s website. These sites offer printable handouts, videos, and audio guides on topics like medications, falls prevention, and chronic disease management. All are tested with older adults and follow national health literacy standards.

What is the ‘teach-back’ method?

The teach-back method is a simple way to check if someone understood health instructions. After explaining something - like how to take a pill - ask the person to explain it back in their own words. For example: ‘Can you show me how you’ll take this medicine each day?’ This helps catch misunderstandings before they lead to mistakes. Studies show it improves adherence and reduces hospital visits.

Why do seniors often not ask for clarification?

Many seniors don’t ask questions because they feel embarrassed or afraid they’ll seem stupid. Others worry they’ll waste the doctor’s time. A 2022 National Council on Aging survey found that 51% of older adults admit to staying silent when confused. That’s why materials should include prompts like ‘It’s okay to ask’ or ‘Write down your questions.’ Caregivers can help by saying, ‘Let’s ask the doctor together.’

How can technology help senior patient education?

Technology helps when it’s designed for seniors. Voice-activated videos, like those in the NIA’s Go4Life program, let users say, ‘Play my balance exercises,’ and start them without touching a screen. Apps with large buttons, simple menus, and audio instructions are useful. But many digital tools are too complex. The best approach combines tech with printed materials - for example, a QR code on a handout that leads to a simple video explanation.

16 Comments