Imagine a drug that saves lives - but costs $10,000 a month. Now imagine that same drug could cost $200 if generics were allowed in. That’s the reality of evergreening - a legal strategy used by big pharma to keep prices high by delaying generic competition, even when the original patent is about to expire.

What Exactly Is Evergreening?

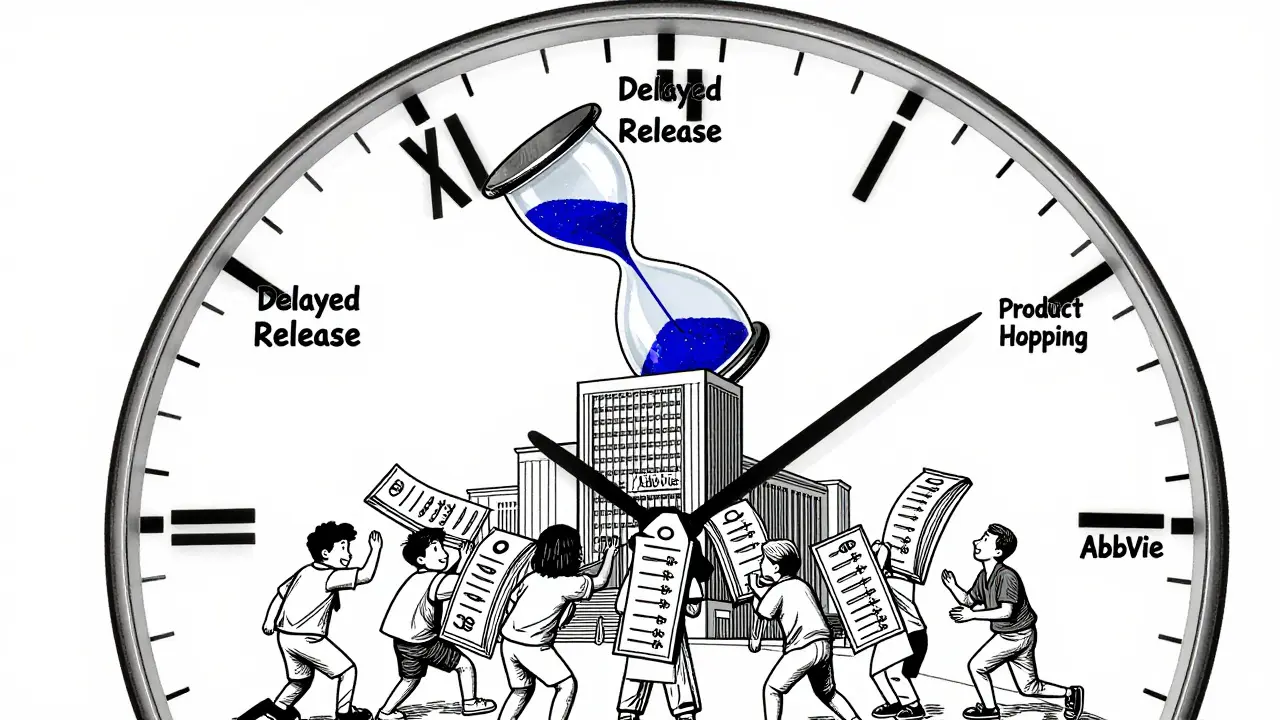

Evergreening isn’t about inventing new medicines. It’s about making tiny changes to old ones - a new pill coating, a slightly different dose, a delayed-release version - and then filing a new patent. These changes often offer no real benefit to patients, but they give companies a fresh 20-year monopoly. The original patent on a drug lasts 20 years from filing. But with evergreening, companies stack on extra protections, sometimes extending control for decades.

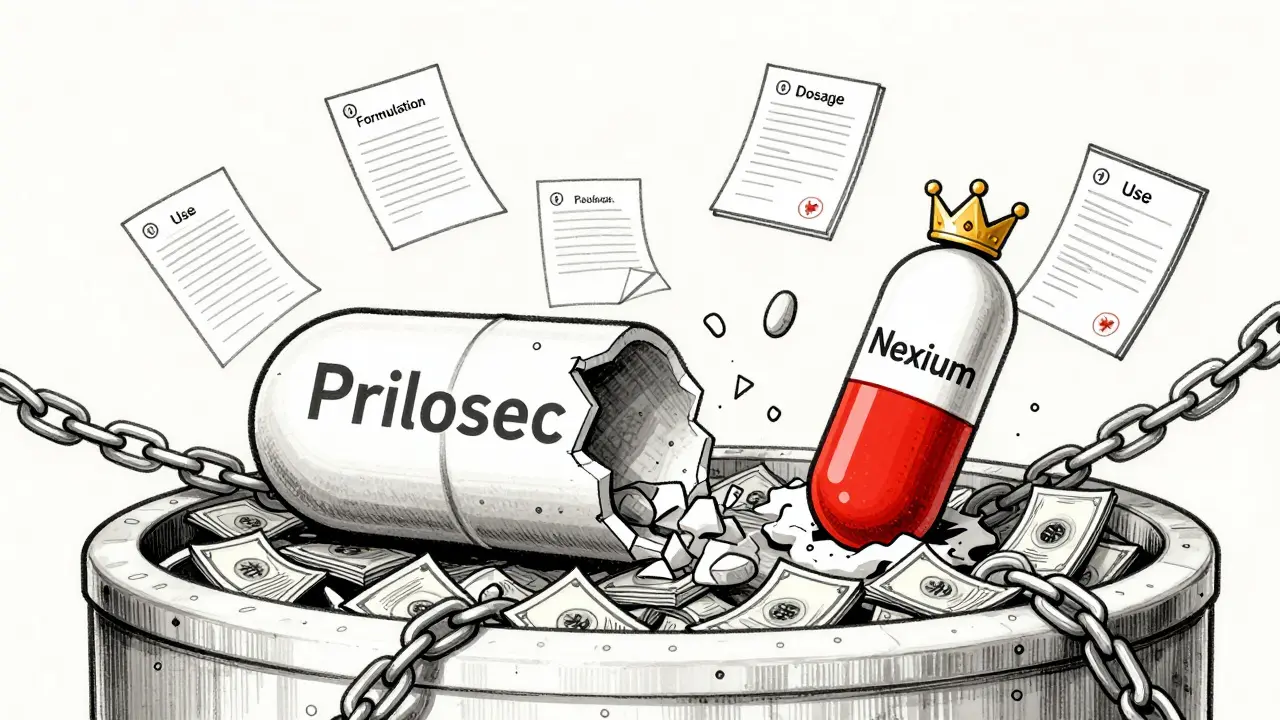

Take AstraZeneca’s Prilosec, a heartburn drug. When its patent neared expiration, they launched Nexium - a chemical tweak that worked almost the same way. Nexium wasn’t better. But it was new. And it came with a new patent. By the time Nexium’s patent expired, AstraZeneca had already piled on six more patents around it. Together, those patents extended market control for over 90 years across just six drugs.

How Do Companies Pull This Off?

There’s a playbook. Here’s how it works in practice:

- Minor formulation changes - Switching from a tablet to a capsule, or adding a slow-release layer. Even if the active ingredient is identical, this qualifies as a "new delivery system."

- New dosage combinations - Mixing two old drugs into one pill. Sounds convenient? It is - but only if the combination wasn’t obvious. Courts often disagree on that.

- Patenting new uses - If a drug originally treated high blood pressure, but later studies show it helps with migraines, companies file for a new indication. This adds three years of exclusivity under U.S. law.

- Pediatric exclusivity - If a company runs studies on kids (even if the drug was never meant for them), they get an extra six months. This is legal - but often done just to buy time.

- Product hopping - This is the most aggressive tactic. Companies stop making the old version, push doctors to switch to the new one, and then sue generics for copying the old drug. Patients and insurers get stuck paying for the new version, even if it’s no better.

AbbVie’s Humira is the poster child. For a drug treating rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s, and psoriasis, AbbVie filed 247 patents. Over 100 were granted. Each one created a new legal hurdle for generics. The result? Humira made $40 million a day at its peak - all because no generic could break in.

Why Is This a Problem?

Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper - they’re just as safe and effective. The FDA requires them to prove bioequivalence. That means they work the same way in your body. But evergreening blocks them.

When a generic enters the market, prices drop 80-85% within the first year. That’s not theory - it’s data. In the U.S., Medicare spends $100 billion a year on brand-name drugs. If generics were allowed in on time, that number could drop by $40 billion.

Patients suffer. A diabetic in Australia might pay $500 a month for insulin because the maker extended patents through minor changes. In the U.S., some patients ration insulin because they can’t afford it. That’s not a failure of healthcare - it’s a failure of policy.

And it’s not just about money. Evergreening delays access in low-income countries. A drug that’s generic in Canada might still be under patent in India or Nigeria because companies use trade rules to block parallel imports.

Who’s Behind This?

It’s not rogue startups. It’s the biggest names in pharma: AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson. These companies have teams of patent lawyers and chemists working five to seven years before a patent expires, looking for ways to tweak the drug just enough to qualify for a new patent.

They don’t need to invent. They just need to file. The cost of a patent application? Around $10,000. The cost of developing a new drug? $2.6 billion. Evergreening is cheap. And the payoff? Billions.

Harvard researchers found that 78% of new patents for prescription drugs are for existing drugs - not new ones. That’s not innovation. That’s legal engineering.

Is There Any Pushback?

Yes - but it’s slow.

In 2022, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission sued AbbVie over Humira’s patent thicket, calling it "anticompetitive." The case is still ongoing. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 let Medicare negotiate prices for some high-cost drugs - a direct hit to evergreening’s profit model.

The European Medicines Agency now demands proof of "significant clinical benefit" before granting extra exclusivity. That’s a big shift. In the U.S., the USPTO has started rejecting patents for "obvious" changes - like switching from a tablet to a capsule when no new effect is proven.

But companies adapt. Now they’re patenting genetic tests that predict who responds to a drug. Or using nanotechnology to make delivery systems that generics can’t easily copy. The goal isn’t to stop evergreening - it’s to make it harder to challenge.

What Can Be Done?

Patients can’t fight this alone. But policy can.

- Require real clinical benefit - Don’t give extra exclusivity just because the pill looks different. Require proof the new version is better for patients.

- Limit patent stacking - If a company files more than 10 patents on one drug, trigger automatic review.

- Speed up generic approval - The FDA should fast-track generics when patents are clearly weak.

- End product hopping - If a company discontinues the original drug to force patients to the new version, regulators should allow generics of the original to enter.

Some countries are already doing this. Canada and the UK have stricter rules. They don’t stop innovation - they just stop games.

The Bigger Picture

Pharma companies argue they need patents to fund research. And yes - developing a new drug is expensive. But evergreening isn’t funding research. It’s funding profits.

The money spent on patent lawyers and marketing tweaks could be spent on actual innovation. Instead of tweaking old drugs, why not invest in new ones for Alzheimer’s, antibiotic resistance, or rare diseases?

Every year a drug stays off the market because of evergreening, thousands of people pay more than they should. Or go without.

It’s not about being anti-pharma. It’s about being pro-patient.

Is evergreening illegal?

No, it’s not illegal - but it’s controversial. Courts and regulators have started rejecting patents that don’t show real innovation. In the U.S., the USPTO and FTC are cracking down on obvious tweaks and patent stacking. But until laws change, companies can still use these tactics legally.

Do evergreened drugs work better than generics?

Almost never. In most cases, the active ingredient is identical. A delayed-release version might last longer, but it doesn’t treat the condition better. Studies show patients get the same results from generics. The difference is price - not performance.

How long can a drug stay protected through evergreening?

It varies, but it can be decades. The original patent lasts 20 years. But with additional exclusivity for pediatric studies, new formulations, and new uses, some drugs stay protected for 30, 40, or even more years. Humira’s patents are set to last until 2034 - nearly 25 years after its first approval.

Can I ask my doctor for a generic instead?

Yes - and you should. If your prescription is for a brand-name drug, ask if a generic exists. Many doctors don’t know about evergreening, so they assume the brand is necessary. But if the active ingredient is the same, the generic is just as safe and effective. Insurance often covers generics at a fraction of the cost.

Are there any drugs that aren’t affected by evergreening?

Yes - older drugs that never had strong patent protection, or those where no company bothered to file extra patents. Many antibiotics, antihypertensives, and diabetes drugs from the 1990s are now generic. But the most profitable drugs - the ones used daily by millions - are the ones most likely to be evergreened.

14 Comments