For decades, cancer treatment meant chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery-harsh methods that attacked the body as much as the disease. But today, a new kind of fight is happening inside us: one where the body’s own immune system is trained to hunt down cancer cells. Two breakthroughs are leading this charge: checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapy. They don’t just kill cancer. They change how the immune system sees it.

How Cancer Hides From Your Immune System

Your immune system is always watching for trouble. T-cells, the body’s special soldiers, are supposed to spot abnormal cells and destroy them. But cancer is sneaky. It learns to trick the immune system into thinking it’s harmless. One way it does this is by flipping on invisible switches called checkpoint proteins. These proteins, like PD-1 on T-cells and PD-L1 on cancer cells, act like brakes. When they connect, the T-cell shuts down. No attack. No destruction. Just silence. This isn’t a glitch. It’s survival-for the cancer. By 2025, researchers know that up to 70% of solid tumors use this trick. Some tumors even produce so much PD-L1 that they drown out any immune signal. Others lower their visibility by hiding key markers that T-cells use to identify them. That’s why traditional treatments often fail: they don’t fix the immune system’s blindness.Checkpoint Inhibitors: Releasing the Brakes

Checkpoint inhibitors are drugs designed to cut those brakes. They’re monoclonal antibodies-lab-made proteins that lock onto specific checkpoint proteins and block them. Think of them as tiny wrenches thrown into a machine that’s been deliberately jammed. There are three main types:- Anti-PD-1 (like pembrolizumab and nivolumab): Block the PD-1 receptor on T-cells.

- Anti-PD-L1 (like atezolizumab and durvalumab): Block the PD-L1 protein on cancer cells.

- Anti-CTLA-4 (like ipilimumab): Works earlier in the immune response, helping T-cells activate in the first place.

CAR-T Cell Therapy: Engineering Your Own Soldiers

If checkpoint inhibitors are about removing barriers, CAR-T therapy is about building better fighters. Here’s how it works: First, doctors take a sample of your blood-usually through a process called leukapheresis. They pull out your T-cells, the very cells that should be killing cancer. Then, in a lab, those cells are genetically modified. A synthetic receptor, called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), is added to their surface. This CAR is designed to recognize one specific protein on cancer cells-like CD19 on B-cell leukemias or BCMA on multiple myeloma. The modified T-cells are grown in huge numbers-billions of them. Then, after you get a round of chemotherapy to clear space in your immune system, they’re infused back into your body. These aren’t just T-cells anymore. They’re supercharged, targeted missiles programmed to find and destroy cancer cells with precision. The results? Stunning in blood cancers. For kids with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), complete response rates hit 80-90%. In adults with certain lymphomas, over 60% go into remission. The first CAR-T therapy, tisagenlecleucel, was approved by the FDA in 2017 for ALL. Since then, five more have followed. But CAR-T isn’t perfect. It’s expensive-between $373,000 and $475,000 per treatment. It takes 3-5 weeks to make. And it comes with serious risks. Half to 70% of patients develop cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a dangerous flood of immune chemicals that causes high fever, low blood pressure, and breathing trouble. One in five gets neurotoxicity-confusion, seizures, or trouble speaking. That’s called ICANS. Hospitals need special training to manage it. The American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy says centers must treat at least 10-15 patients before they’re truly proficient.

Why CAR-T Struggles With Solid Tumors

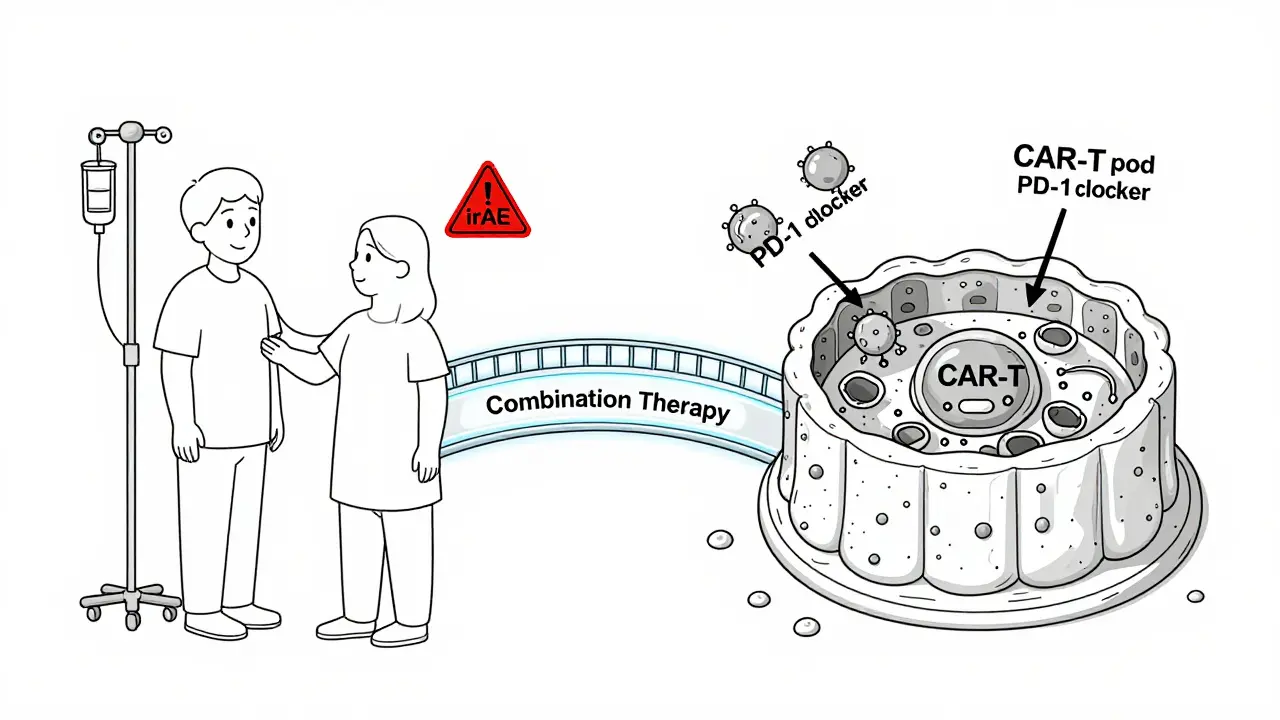

You might wonder: if CAR-T works so well in blood cancers, why not lung, breast, or colon cancer? Solid tumors are tougher. They create a hostile environment. Think of it like a fortress with moats, walls, and poison gas. The tumor microenvironment floods the area with immune-suppressing chemicals. T-cells can’t get in. Even if they do, they get tired. They become “exhausted.” And many solid tumors don’t have clear targets. CD19? Only on blood cells. Breast cancer? No single protein that’s unique to the tumor and nowhere else. Current CAR-T trials for solid tumors show response rates under 10%. That’s why researchers are trying new tricks: arming CAR-T cells with extra tools. Some are engineered to secrete IL-12, a cytokine that wakes up other immune cells. Others are designed to block PD-1 right inside the tumor-so the checkpoint inhibitor works only where it’s needed, not everywhere in the body. A 2018 study showed that CAR-T cells modified to release their own PD-1 blocker reduced immune side effects by 37% in mice-and boosted tumor killing. That’s the future: smarter, localized attacks.Combining the Two: The Next Big Leap

The real breakthrough might not be one therapy alone-but both together. Checkpoint inhibitors bring T-cells into the fight. CAR-T cells give them a precise target. Put them together, and you’re not just removing brakes-you’re adding engines. As of March 2024, 47 active clinical trials are testing this combo. Sixty-eight percent focus on solid tumors. Early results are promising. In melanoma and lung cancer, response rates jump from 30% with checkpoint inhibitors alone to 50-60% when CAR-T is added. But there’s a risk. Combine them, and side effects multiply. CRS and irAEs can overlap. That’s why the new wave of research focuses on making CAR-T cells deliver the checkpoint blocker themselves-right at the tumor. This way, you get the power of both therapies without flooding the body with drugs. One study in 2024 showed this approach cut lung inflammation by 42% compared to giving both drugs separately. It’s not just safer-it’s more effective.

Access, Cost, and Inequality

These therapies aren’t just science-they’re social issues. CAR-T therapy is only available at about 15% of U.S. cancer centers, even though academic hospitals handle 87% of all treatments. That means patients in rural areas or smaller cities often can’t get it. A 2020 review found Black patients were 31% less likely to receive CAR-T than White patients. Medicaid patients were 23% less likely. Checkpoint inhibitors are easier to get. They’re shipped like any other drug. But even then, cost and insurance hurdles block access. The global immunotherapy market hit $128 billion in 2022. Checkpoint inhibitors made up $83.5 billion of that. CAR-T? Just $6.4 billion. Why? Because it’s complex. It’s personalized. It’s slow. And it’s not scalable yet. New “off-the-shelf” CAR-T therapies are coming-made from donor cells, not your own. That could cut cost and wait time. But they’re still experimental. And even if they work, will they be affordable?What’s Next?

The next five years will be about three things:- Better targets: Finding proteins that exist only on cancer cells, not healthy ones.

- Smarter engineering: CAR-T cells that resist exhaustion, survive longer, and fight the tumor’s defenses.

- Local delivery: Turning CAR-T cells into mini-pharmacies that release checkpoint blockers, cytokines, or drugs exactly where needed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T therapy the same thing?

No. Checkpoint inhibitors are drugs given through an IV that remove brakes on your immune system. CAR-T therapy is a personalized treatment where your own T-cells are removed, genetically changed in a lab to target cancer, and then put back into your body. One is a drug. The other is a living medicine.

Which cancers respond best to CAR-T therapy?

CAR-T works best in certain blood cancers: B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in children and young adults, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. Response rates can reach 80-90% in ALL. For solid tumors like lung, breast, or colon cancer, success is rare-still under 10% in most trials.

Why is CAR-T therapy so expensive?

Each CAR-T treatment is custom-made for one patient. It requires collecting your blood, genetically modifying your cells in a sterile lab, growing billions of them, testing for safety, and then reinfusing them-all within 3-5 weeks. The process needs specialized facilities, trained staff, and complex quality controls. That’s why it costs between $373,000 and $475,000. Checkpoint inhibitors are mass-produced drugs, so they’re cheaper.

What are the biggest side effects of CAR-T therapy?

The two most serious are cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). CRS causes high fever, low blood pressure, and trouble breathing. ICANS can lead to confusion, seizures, or loss of speech. About half to 70% of patients get CRS, and 20-40% get ICANS. Both need immediate medical care. Most patients recover with proper treatment.

Can I get these treatments if I live outside a big city?

Checkpoint inhibitors are widely available at most cancer centers. CAR-T therapy is not. In the U.S., only about 15% of cancer centers offer it, and they handle nearly 90% of all treatments. In Australia, access is limited to major hospitals in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth. Travel and insurance approval are often required. Patients in regional areas may need to relocate temporarily for treatment.

Is immunotherapy a cure for cancer?

For some patients, yes. A small but growing number of people with advanced melanoma or leukemia have been in remission for over a decade after immunotherapy. But it’s not a cure for everyone. Many cancers still return. The goal now is to make responses last longer-and to help more people benefit. For now, it’s one of the most powerful tools we have, but not a magic bullet.

9 Comments