Pediatric Side Effect Detection Calculator

Side Effect Detection Calculator

Calculate how many hospitals are needed to detect rare side effects in children and how quickly a safety network can identify potential problems

When a child is given a new medication or undergoes a medical procedure, doctors don’t always know what might go wrong. Unlike adults, kids aren’t just small versions of grown-ups-their bodies react differently. A drug that’s safe for a 40-year-old might cause unexpected side effects in a 5-year-old. Yet for decades, pediatric drug safety was an afterthought. Clinical trials rarely included children. When they did, data was scattered, slow to collect, and often too limited to catch rare but serious reactions. That changed when researchers realized: pediatric safety networks are the only way to truly understand how treatments affect kids.

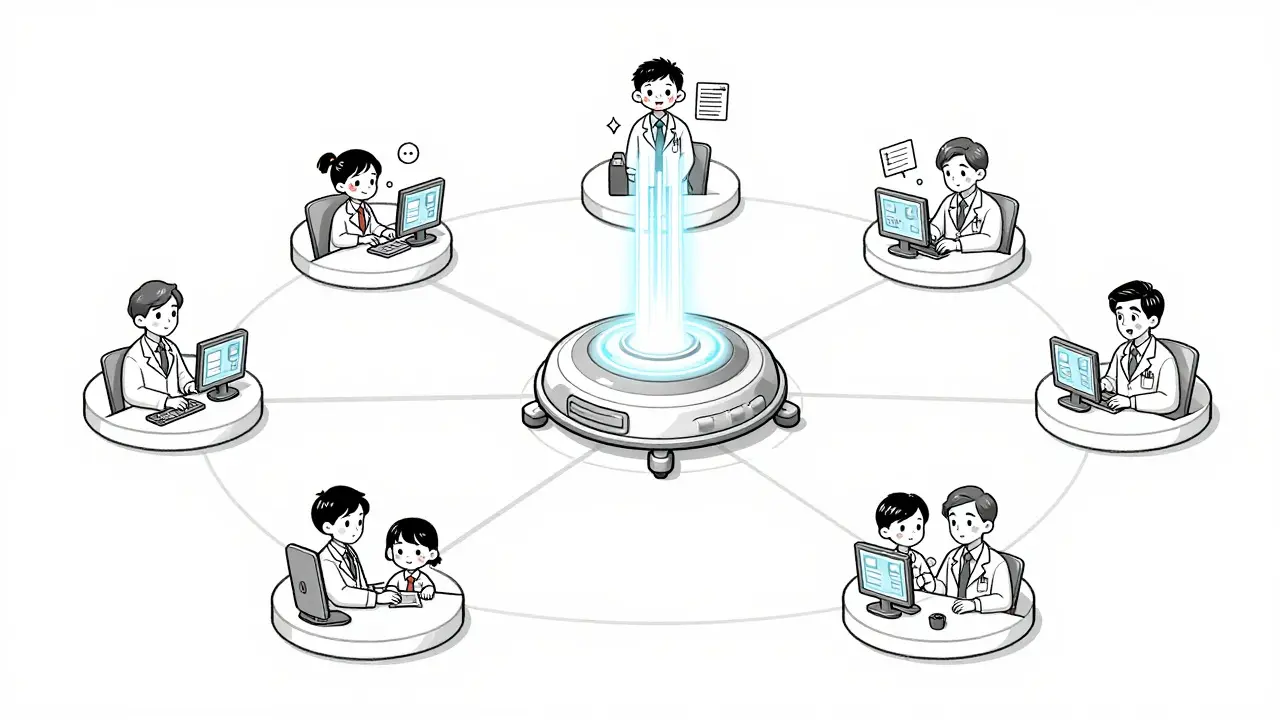

These aren’t just research groups. They’re tightly organized, multi-hospital systems designed to catch side effects in real time. Think of them as early-warning systems for children’s health. One of the most influential was the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) a federally funded network established by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in 2014 to study treatment safety in critically ill children. It brought together seven major pediatric hospitals across the U.S., a central data hub, and strict oversight teams. Their job? Not just to test new treatments, but to watch every single side effect-no matter how small.

How These Networks Catch Side Effects That Hospitals Miss

Hospitals alone can’t spot rare side effects. If a drug causes a reaction in 1 in 1,000 kids, one hospital might see it once in five years. But seven hospitals together? That’s seven chances to catch it. The CPCCRN used a centralized Data Coordinating Center (DCC) to collect, clean, and analyze data from all sites. This wasn’t just about numbers. They tracked symptoms, lab results, and even parent reports using standardized forms. If a child developed a strange rash after a new antibiotic, the system flagged it immediately. The DCC didn’t just store data-it ran statistical models to predict whether the side effect was random or a real pattern.

Another layer was the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB). This group of independent experts-doctors, statisticians, ethicists-met regularly to review all safety data. They had the power to pause a study if risks outweighed benefits. In one case, a trial for a new sedative in ICU kids was temporarily halted after the DSMB noticed a spike in low blood pressure. The team adjusted the dosage, and the study resumed safely. Without this centralized oversight, that pattern might have been missed for years.

From Hospitals to Communities: The Child Safety CoIIN Model

Not all pediatric safety work happens in hospitals. The Child Safety Collaborative Innovation and Improvement Network (CoIIN) a HRSA-funded initiative focused on preventing injuries and tracking unintended consequences of safety programs in children took a different approach. Instead of studying drugs, it looked at real-world risks: car seat misuse, falls at home, youth violence prevention. They worked with 16 states, each running teams of public health workers, educators, and clinicians. These teams didn’t just collect data-they changed how they worked based on what they found.

One team in Ohio was running a program to reduce sexual violence among teens. They thought their “Green Dot” workshops were working. But when they started tracking outcomes in real time, they saw something surprising: girls in dating relationships were still reporting abuse at the same rate. The data forced them to rethink. They added new modules on healthy relationships and consent, and within a year, reports of unsafe situations dropped by 30%. This is the power of these networks: they don’t just measure outcomes-they adapt in real time.

Why Traditional Clinical Trials Fall Short for Kids

Randomized controlled trials-the gold standard in medicine-don’t work well for children. It’s unethical to give one group a placebo when a child is critically ill. It’s hard to recruit enough kids for rare conditions. And side effects can take months or years to show up. That’s where collaborative networks shine. They use real-world data from thousands of kids across different settings. A child in Chicago might get the same treatment as one in Atlanta, and if both have the same rare reaction, the network picks it up. This approach helped uncover that a common IV antibiotic caused liver enzyme spikes in underweight infants-a finding that led to updated dosing guidelines.

According to a 2013 study in Academic Pediatrics by Carole M. Lannon and Laura E. Peterson, these networks are the only way to generate safety evidence where traditional trials can’t go. They’re especially vital for kids with rare diseases, those on multiple medications, or those in intensive care. The study found that networks reduced the time it took to detect a side effect by over 60% compared to single-center studies.

How Data Is Collected and Protected

Every network has strict rules. Data is collected through digital forms built into hospital systems. For the CPCCRN, each site used identical data templates-so a fever in one hospital meant the same thing as a fever in another. All data was encrypted and transmitted through secure HIPAA-compliant channels. The DCC didn’t store names-only medical IDs, dates, and outcomes. Even the DSMB saw anonymized data. Parents weren’t asked to sign consent for every data point. Instead, networks used broad consent frameworks approved by ethics boards, allowing ongoing safety monitoring without repeated paperwork.

The CoIIN used similar methods but focused on community settings. Schools, clinics, and youth centers used simple paper forms or tablets to log incidents. A fall from a playground? A car seat mislatched? A teen reporting dating violence? Each was logged with location, time, and outcome. These weren’t just reports-they became triggers for change. One state added mandatory safety training for coaches after data showed a spike in injuries during after-school sports.

What Happened After the Original Networks Ended

The CPCCRN’s funding ended in 2014. The CoIIN wrapped up its last cohort in 2019. But that doesn’t mean the work stopped. The infrastructure, tools, and methods didn’t disappear-they got absorbed into larger systems. The NICHD launched the Pediatric Trials Network a successor to CPCCRN using updated UG3/UH3 funding mechanisms to continue multi-site pediatric safety research, which now runs over 30 active studies on drugs, devices, and surgical procedures. The CoIIN’s change packages and real-time data tools were adopted by state health departments nationwide. Today, nearly every major children’s hospital in the U.S. has its own internal safety monitoring system modeled after these networks.

What’s new now? Integration. Networks are starting to link hospital data with school health records, pharmacy logs, and even wearable devices. A child with asthma might now have their inhaler use tracked alongside ER visits and sleep patterns-all fed into a single safety dashboard. This lets doctors see not just if a drug works, but how it affects daily life over time.

The Real Impact: Fewer Kids Hurt Because of Better Data

These networks didn’t just produce papers. They saved lives. After CPCCRN data showed that certain painkillers caused breathing problems in toddlers after surgery, hospitals changed their protocols. The result? A 40% drop in post-op respiratory events in participating hospitals. CoIIN’s work led to 12 states updating their car seat laws based on real-world misuse data. One state saw a 50% reduction in preventable injuries after adopting a simple checklist for home safety visits.

The lesson? You can’t protect kids if you don’t see what’s happening. These networks turned silence into data, and data into action. They didn’t wait for a tragedy to happen. They built systems to find the warning signs before they became emergencies.

What’s Next for Pediatric Safety Research

The future lies in automation and long-term tracking. Imagine a child’s electronic health record that automatically flags a new rash after a vaccine, compares it to thousands of other cases, and alerts the nearest pediatric safety hub-all within hours. That’s already being tested. Researchers are also linking networks across countries. A side effect seen in Australia might be confirmed in Canada or Brazil, giving doctors global evidence faster.

But the biggest challenge remains funding. These networks rely on federal grants. When funding ends, momentum slows. The key now is proving their value in dollars and lives. Every dollar spent on these networks saves an estimated $7 in future healthcare costs by preventing avoidable harm. That’s not just science-it’s smart policy.

15 Comments