Over 95% of all generic drug shortages in the US involve generic medications. This isn't a random glitch-it's a systemic failure in how these essential medicines are made and delivered. When hospitals run out of common antibiotics or chemotherapy drugs, patients face real risks. The reasons behind these shortages are complex, rooted in manufacturing problems, supply chain weaknesses, and economic pressures. Let's break down exactly what's happening.

Manufacturing Problems: The Leading Cause of Shortages

According to the FDA, a drug shortage occurs when there's a 'temporary or permanent decline in the supply of a drug product below what is needed for the U.S. health care system'. Manufacturing issues account for 62% of all shortages, according to FDA data from 2020. This includes:

- Facility contamination events

- Equipment failures

- Compliance issues requiring corrective actions that halt production

For example, a single contamination incident at a sterile injectable plant can shut down production for months. The FDA often finds serious problems like improper cleaning procedures or inadequate quality controls. These issues don't just affect one drug-they ripple through the entire supply chain. In 2018, the FDA recorded the highest number of drugs entering shortage during the 2018-2023 period, with 2020's pandemic disruptions causing the second-highest count.

Geographic Concentration Creates Critical Vulnerabilities

About 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing happens in China and India. API is the key component of a drug that provides its therapeutic effect. This concentration creates massive risk. If a natural disaster, trade dispute, or pandemic disrupts production in these regions, shortages ripple across the globe. A single supplier for a critical API can cause widespread problems. University of Toronto and Pitt researchers found that one in five shortage reports involves sole-sourced drugs. When only one factory makes a particular ingredient, there's no backup plan when something goes wrong. The NCBI Bookshelf (2023) notes that approximately half of FDA-registered finished dosage form manufacturing facilities and most API manufacturing facilities are located outside the United States.

Economic Pressures Drive Manufacturers Out

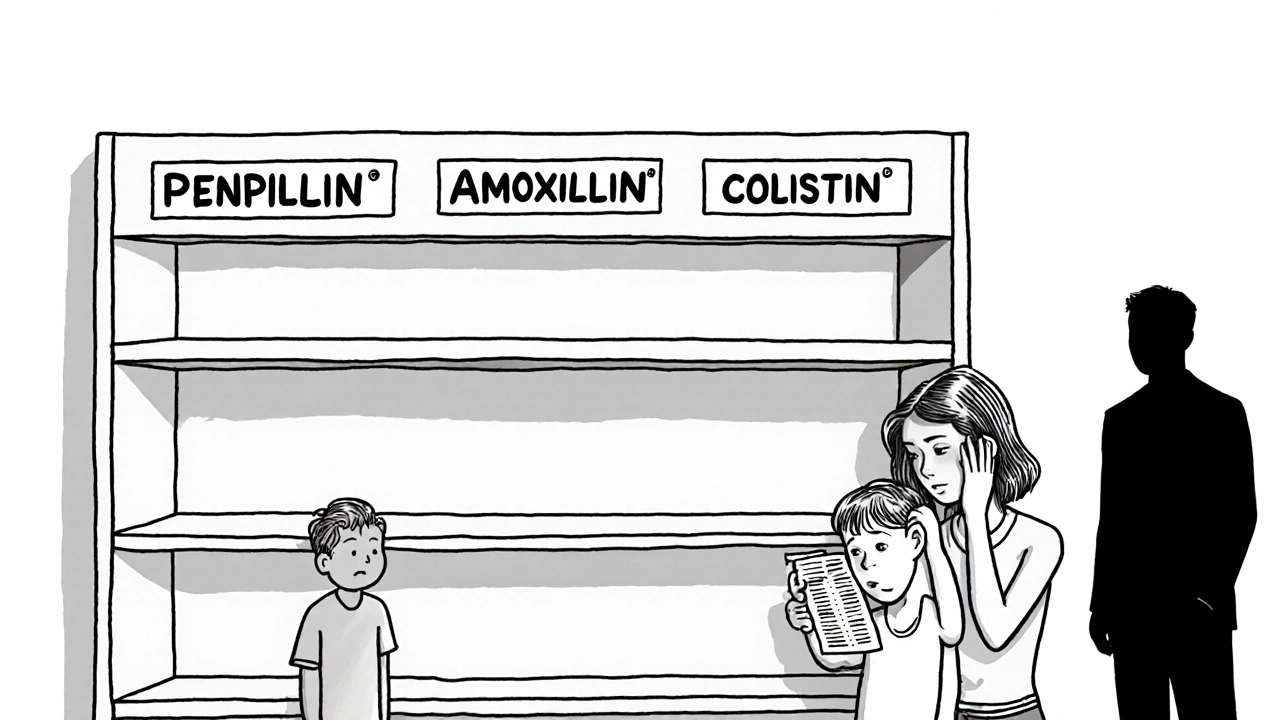

Profit margins for generic drugs are often below 15%, compared to 30-40% for branded drugs. This makes it hard for manufacturers to invest in modern equipment or maintain quality systems. The Association for Accessible Medicines reports over 3,000 generic product discontinuations since 2010. Manufacturers leave the market when they can't make enough money. This creates a vicious cycle: fewer suppliers mean less competition, which drives prices lower and pushes more companies out. The HHS White Paper (2023) states that 'low and/or unpredictable sales volumes, prices, and profit margins for many generic drugs' create a shortage-prone system. Companies simply can't afford to stay in business when margins are too thin.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers Control the Market

PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) control about 85% of prescription drug spending in the US. The Federal Trade Commission's July 2023 interim staff report documented that PBMs make 'critical decisions about access to and affordability of life-saving medications without transparency or accountability to the public'. They often prioritize cheaper drugs in short supply over those in adequate supply, worsening shortages. Hospitals and pharmacies have little leverage to negotiate better terms, leaving them vulnerable when supplies run low. This market concentration creates a system where shortages are amplified rather than mitigated.

US vs Canada: Different Approaches

Canada handles drug shortages better than the US. A 2023 study by University of Toronto and University of Pittsburgh researchers found that while both countries face similar supply chain issues, Canada has stronger cooperation between regulators, health systems, and manufacturers. Canada's strategic pharmaceutical stockpile specifically addresses shortages, while the US stockpile is only for acute emergencies like terrorism. This difference means Canadian patients rarely face the same level of disruption. Dr. Mina Tadrous, lead author of the study, emphasizes that 'the pharmaceutical supply chain is global, and every single person who touches a drug is essential, from manufacturers to port workers to pharmacists'.

Current Policies and Solutions

The RAPID Reserve Act (S.2510/H.R.6802), introduced in 2023, aims to create strategic reserves for critical generic drugs. The HHS (Department of Health and Human Services) has identified market forces as a key driver of shortages. Meanwhile, the AmerisourceBergen White Paper (2023) highlights the need for diversified manufacturing sources. Experts agree that without fundamental reforms, shortages will continue. The AMA advocates for 'diversified manufacturing and more resilient supply chains' as essential solutions, while Dr. Lisa Maillart from Pitt's Swanson School of Engineering stresses the need for 'comprehensive, interdisciplinary collaboration between Pharmacy, Medicine, Public Health, and Industrial Engineering'.

Why do generic drugs have shortages more often than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs face higher risks because they operate on razor-thin profit margins (often below 15%) compared to branded drugs (30-40%). Manufacturers have less incentive to invest in maintaining production lines for generics, leading to fewer suppliers and higher vulnerability to disruptions. Additionally, the generic market has more competition, causing prices to drop further and pushing companies out of the market. This economic pressure creates a cycle where manufacturers abandon lower-margin products even during shortages.

How does geographic concentration affect drug availability?

About 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing occurs in China and India. This concentration creates major risks-natural disasters, trade disputes, or pandemics in these regions can disrupt global supplies. For example, during the 2020-2021 pandemic, supply chain delays from Asia caused widespread shortages of critical medications like antibiotics and chemotherapy drugs. A single supplier for a critical API can cause widespread problems, with one in five shortage reports involving sole-sourced drugs.

What role do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) play in shortages?

PBMs control 85% of prescription drug spending in the US. They often prioritize cheaper drugs in short supply over those in adequate supply, worsening shortages. The FTC's 2023 report found PBMs make critical decisions without transparency, sometimes forcing hospitals to use drugs that are already scarce. This lack of accountability creates a system where shortages are amplified rather than mitigated, leaving healthcare providers with limited options during critical shortages.

Are there any solutions being implemented to address shortages?

The RAPID Reserve Act (S.2510/H.R.6802) aims to create strategic reserves for critical generic drugs. The FTC is investigating PBMs for market concentration issues. However, experts say these steps aren't enough without broader reforms. Solutions include incentivizing domestic manufacturing, diversifying API sources, and adjusting economic incentives to keep manufacturers in the market. Without systemic changes, shortages will continue to disrupt patient care.

Why doesn't the US have a stockpile for drug shortages like Canada?

The US Strategic National Stockpile is designed only for acute emergencies like terrorism or mass casualties, not ongoing drug shortages. Canada's stockpile specifically addresses shortages of essential medications. This difference means Canadian healthcare systems can quickly access reserves during shortages, while US hospitals often have no backup when supplies run low. The HHS White Paper (2023) notes that the US system is 'shortage-prone and too slow to respond to shortages' compared to Canada's more cooperative approach.

10 Comments